By Alice Moreno

Stepping onto the second floor of the Museum of Moving Image (MoMI) in Astoria, Queens felt as if I stepped into a sort of time machine, magically transported back to the 90s where instead of smartphones and social media, there were camcorders, boxy TVs, and old-school rap and punk music blasting through the speakers. The common theme at this exhibit was skaters, who joined together back in the days to film themselves at their local park with just a camcorder, their impressive tricks and a dream.

This dream is the foundation upon which the skating community is built today. What was once a small community featuring your local skater-next-door hitting up the abandoned pool with a small filming crew, is now an amalgamation of its rising popularity. Currently, skating culture is seen everywhere, including high-fashion brands like Supreme, street-style becoming a fashion staple, Oscar-award nominated films, the popular gaming series “Tony Hawk Pro Skater,” and the inclusion of skating at the Olympics.

The most important part of celebrating skating culture and its emergence in popular culture is remembering where it all started. The exhibition, “Recording the Ride: The Rise of Street-Style Skate Videos,” does exactly that.

Installed at the MoMI’s video amphitheater, the exhibition explores the history of skating videos, from its emergence in the mid-1980s to its increasing popularity in the 1990s. Throughout the exhibition, these videos were played on CRT-TV’s, with the earliest being from 1984 and the latest from 2021. The videos were notable for being filmed on camcorders. Due to the high-speed nature of skating, filmmakers had to be up to speed. Using camcorders — which were portable — made it easy for them to move around, using a wide-angle lens to siphon every second of their moves.

“It’s a great opportunity to show off the amazing creativity and the kind of exuberance and the great DIY spirit of the skate video,” said Barbara Miller, Deputy Director for Curatorial Affairs at the MoMI. “And to pay homage to [not only] great skaters, but also the filmers and the team managers who were responsible for bringing those videos to life.”

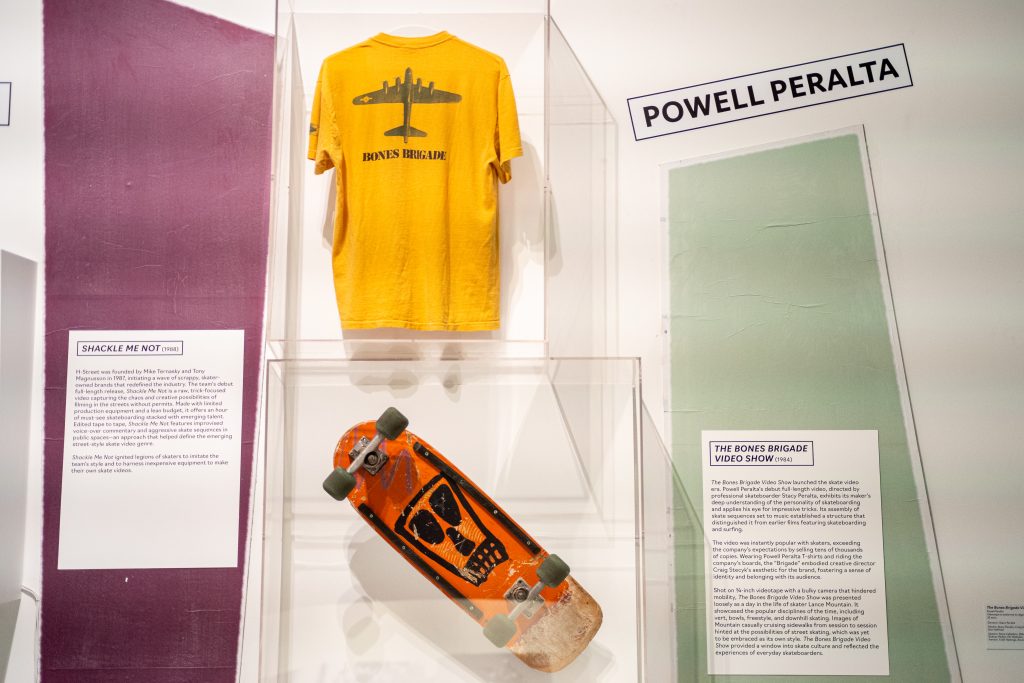

These films were distributed and made by companies such as Zoo York, Powell Peralta, and H-Street — but not for the big screen. These were smaller films, with VHS tapes sold at skate shops, mostly used to be watched at home or even showcased in local art-house theaters. In addition, street style and music set the scene in these videos. Whether it be skaters sporting a “Misfits” t-shirt or videos playing 60s hippie-rock hits like Jefferson Airplane’s “Somebody to Love,” freestyle rap like Ghostface Killah’s “‘93 Freestyle,” or even unexpected tunes such as the mellow “What a Wonderful World,” there is an evident connection between skating and the countercultures of the past.

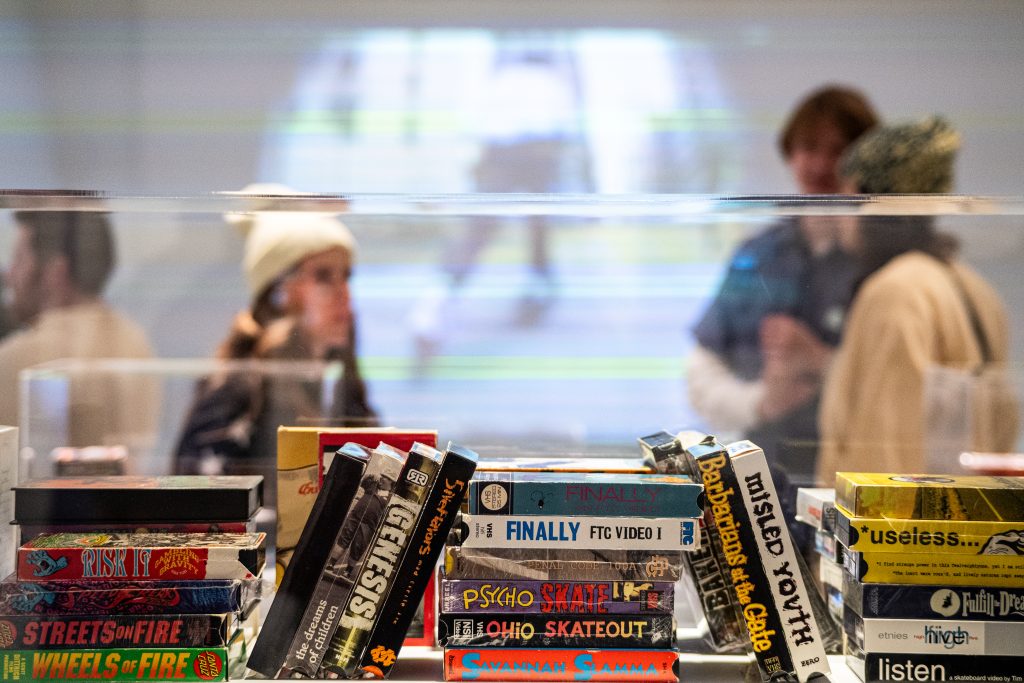

Above the installation, hung a plethora of skateboards. The designs are their art form, all tailored to each skater’s taste — some featured screen-printed images, some had collages of different trinkets and elements, and some even had a simple brand name. Not one skateboard looked alike. Guests were also able to walk past cases filled to the brim with VHS tapes, all including skateboarding content that was also showcased at the amphitheater’s film viewing area. Memorabilia was also present, including camcorders famously used to film the skaters and magazines reporting on the culture.

The effervescent, punk-adjacent skating culture used filmmaking to bring their community together. With the team of skate scene legends Director Jacob Rosenberg; Michaela Ternasky-Holland, daughter of the late Mike Ternasky, founder of Plan B Skateboards; as well as the staff at the MoMI, the dynamic visuals of skaters came to life in this exhibition.