Courtesy FDNY EMS Local 2507

NYC EMS Union Launches Campaign Highlighting Low Pay, High Risk

By MOHAMED FARGHALY

mfarghaly@queensledger.com

The union representing more than 4,000 emergency medical technicians, paramedics and fire inspectors in New York City has launched a public awareness campaign to highlight what it calls “neglect” from City Hall, low pay, and worsening emergency response times that threaten public safety.

FDNY EMS Local 2507 kicked off the #StandWithEMS campaign on October 6, urging New Yorkers to pressure city officials to address long-standing pay disparities and staffing shortages among the city’s medical first responders.

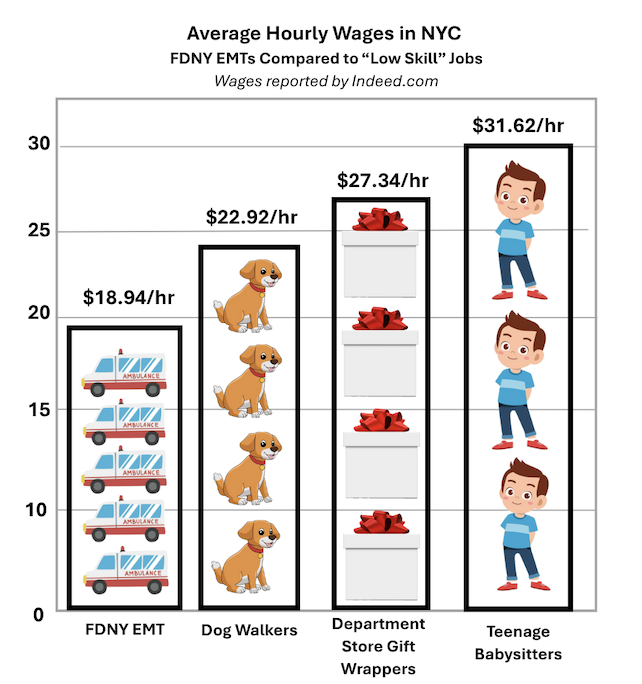

Despite handling 1,630,466 medical emergencies in 2024, a 15.4% increase since the start of the pandemic, EMTs in the city earn just $18.94 an hour — a rate that union leaders say leaves many unable to afford to live where they work.

“We are world-class emergency response medical professionals and the FDNY is the busiest emergency medical response agency in the world,” said Local 2507 Union President Oren Barzilay. “Yet our front-line medical first responders are paid less per hour than most New Yorkers pay to babysitters or dog walkers.”

Barzilay said the situation has pushed EMTs to the brink. “We are literally working for minimum wage,” he said. “They keep passing legislation to improve the minimum wage for the private sector, food service delivery drivers, people in the food industry — they’re all making above what my men and women are making, which is $18 an hour. And if you take away all the deductions after taxes, we’re left with $12 and change.”

Courtesy NYC.Gov

The result, he said, is an attrition rate of about 70% within the first five years on the job. Many EMTs leave for higher-paying work elsewhere — including within the FDNY itself. “Just last Friday, 175 of my men and women resigned in one day to become firefighters, because they will make the same amount of money starting off,” Barzilay said.

The union says the consequences are already visible. According to the Mayor’s Management Report, emergency medical response times are up 1 minute and 47 seconds over the last four years. “People are literally dying because we don’t get there in time,” Barzilay said. He recounted stories shared at City Council hearings of New Yorkers who died waiting for ambulances that took 30 minutes or more to arrive. “This happens every day,” he said.

Barzilay described the situation as both a humanitarian and public safety crisis. “Our EMTs go through four months of training at the EMS Academy. Our paramedics go through nine months of rigorous medical training,” he said. “The training that we receive is how to bring somebody who has passed away back to life. We deal with people who are severely sick or injured, and we sustain their life until we get to the operating room.”

He said many EMS workers now struggle to meet basic needs. “I got men and women who can’t afford to commute to work every day. So they sleep at their station. They sleep at the car. Some are even living in shelters,” he said. “They love the job, but they just can’t afford to live here anymore.”

Barzilay said the pay inequity has persisted across administrations. “The mayor made a promise that he will fix this pay issue. The mayor before that made the same promise. Any mayor makes us the same promise that they will fix the EMS pay gap issues. But once they’re in office, they forget about you,” he said.

He also noted that over 50% of the FDNY EMS workforce are people of color and about 30% are women, arguing that the pay gap has a discriminatory dimension. “It’s discriminatory pay practices,” Barzilay said. “We brought this issue to the federal EEOC, and they ruled in our favor that we have a case and a claim to make against the city of New York.” The union has since filed a class action lawsuit that is now in the discovery phase.

Barzilay warned that as private partners such as Northwell Health withdraw their ambulance units from the city’s 911 system, Queens could soon see longer response times. “Queens is about to lose two ambulances from the private sector that operate under the 911 system,” he said. “Queens will start seeing a rise in response times if this is not corrected either.”

Through #StandWithEMS, Local 2507 is calling on the public to act. “Every citizen who understands our struggles [should] call the mayor’s office and tell them to fix this injustice,” Barzilay said. “We’re not looking for more than anybody else. We’re just looking for equal pay that other first responders have.”

For Queens EMT Esho, the path to emergency medical work began almost by accident. “A close friend told me that if you really don’t know what you’re doing, it’s kind of a safe play — a good introduction,” he said. Unsure of his next step, he applied, took the entry test, and was soon accepted into the 18-week EMS academy. What followed was months of training in anatomy, patient care, and field protocols — combined with the physical demands of daily cardio and endurance tests. “We started off with close to 300 people,” he said. “We graduated with 167.”

When he first stepped into the field, nerves set in. “I didn’t think I was ready. I thought I was gonna mess something up.” But his station quickly made him feel welcome. The station, like most across the city, doubles as both a workplace and a second home — a mix of ambulance bays, small offices, kitchens, and bunk areas for exhausted EMTs trying to grab minutes of rest between long calls.

Each shift begins with a check of the ambulance — “the bus,” as they call it — making sure every piece of gear is ready for the next emergency. Then the calls come. “It’s everything you can think of — cardiac arrests, respiratory distress, even toothaches,” Esho said. “If somebody calls 911, we go.” Some days it’s minor. Other days, it’s life and death. He still remembers one of his first cardiac arrests — a 65-year-old woman who overdosed. “It’s nothing like what you see in training,” he said. “You can’t prepare for the smell, the sight, or the family right there watching.”

In the academy, recruits are exposed to the realities of death early. “They even brought in corpses,” he said, to help prepare students who had never seen a body before. “They said it’s better to see it there than for the first time in the street.”

Now working overnight shifts in Queens, Esho describes EMS as “the ones who come when something happens outside the hospital.” Their job, he said, is to stabilize and transport — to keep patients alive long enough to hand them off to doctors and nurses. Without EMS, he said, “you’d just have a lot more deaths. People panic, they don’t know what to do. We’re the ones that take the problem by the horns and figure it out.”

Like many of his colleagues, he’s aware of the frustration over pay and staffing. Starting EMTs in New York City earn less than $19 an hour. “I kind of still don’t understand why we’re underpaid,” he said. “I see the impact we have every day. We’re helping people who can’t help themselves. But if we can’t afford to live, what’s gonna happen then?”

Esho said the low pay forces many EMTs into difficult personal situations, even as they continue to serve the city. “If we can’t help people anymore, not because we don’t want to, but because we can’t afford to, what happens then? We still have to eat, we still have to live,” he said. He noted that while some employees live with family and avoid rent, many others have no choice but to keep working under physical strain, including mothers, pregnant workers, and people recovering from surgery or injuries. “They’re still going because this is all they have. They’ve been building toward this for so long that they can’t do anything else,” he said. Despite the challenges, Esho acknowledged the dedication of his coworkers: “Even though the pay is low, there are EMS employees who are very passionate about the job and what they do.”

FDNY EMT Sophia Riccio of Battalion 44 in Brooklyn said she joined EMS because “the city needs EMTs that really care about patients. There are not enough EMTs or first responders and there are so many emergency calls all over the city. I love patient care and I love the medical field.”

She described the demands of the job as relentless, explaining, “The daily work conditions are not easy. We are all bombarded with calls and extremely busy, so EMTs are all getting run down. Just to get by, I have had to work close to 60 hours a week and it’s incredibly physically demanding. Mentally, you see a lot of things no one should see on a daily basis and it takes a big toll on all of us. Many EMTs have long commutes to their stations and we are not getting enough sleep. Anyone I talk to that is not EMS finds it disgusting how we get treated and paid. More people are dropping out of the service and calls are getting delayed as a result because there are not enough ambulances anymore. People ask themselves, ‘Why would I want to be in this job seeing these things and do so much for the city just to be paid like this?’”

Barzilay said the union’s ultimate goal is simple: “To get a decent, livable wage so nobody would leave here and go look for other jobs,” he said. “This is not only hurting my men and women, but it’s hurting the public. This is a public crisis.”

Barzilay ended with a plea for solidarity: “We save lives. Somebody needs to save us.”