A Message to the World

A global exhibit brings Gaza’s artists to Brooklyn

BY COLE SINANIAN

In the film Escape from Farida by 27-year-old Palestinian filmmaker Yahya Alsholy, a young man, attractive and clean-cut, sits down for a tea with his girlfriend to the backdrop of palm trees and a sparkling Mediterranean Sea. He shows her his newly taken passport photo, she mocks him for it and the couple share a laugh. Then the mood turns. She looks at him longingly: “I feel like the only thing I’m scared of is what’s going on in your head,” she says. He tells her he’s leaving to pursue a life abroad, and that once he leaves, their relationship must end. “We dreamed for so long, but now we have to wake up to reality,” he says.

The film depicts a timeless human experience imbued with extraordinary weight; their home is the Gaza Strip, where an Israeli offensive has killed at least 66,000 people in under two years, where one of the world’s most densely populated territories has been reduced to rubble and ashes in a matter of months, where drone strikes routinely blow limbs off children and newborns die before their first breaths. In leaving his girlfriend, Alshoy’s protagonist may be, perhaps selfishly, saving his own life.

It’s showing Thursdays through Saturdays until December 20 at Recess, an art space in Brooklyn Navy Yard, along with dozens of other artistic works from Gaza in a roving exhibit called the Gaza Biennale. Currently on view in Athens, Istanbul, Ireland, and Valencia, the Biennale’s Brooklyn exhibit represents its first North American location and a rare opportunity to view the artistic output of a population facing what a growing chorus of global scholars has deemed a genocide.

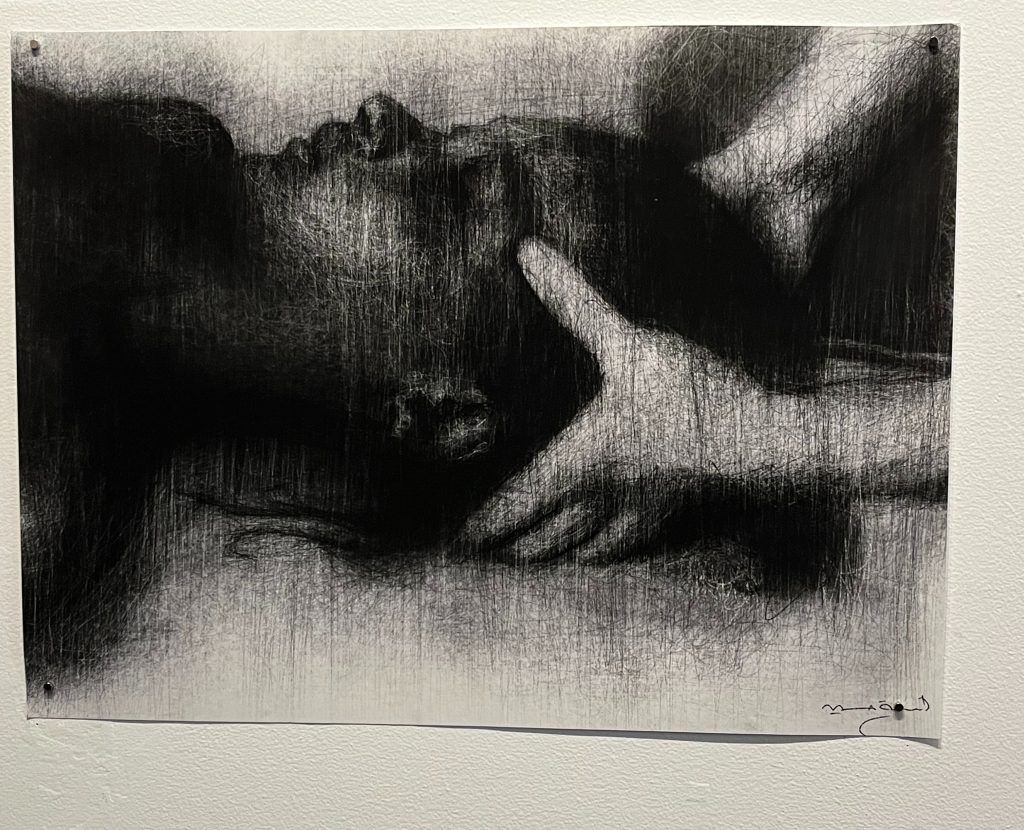

Gaza-born Osama Husein Al Naqqa is a painter, but once the bombardment began painting became unfeasible, so Al-Naqqa turned to digital drawing on his smartphone. As he explains in an interview shown at the Biennale, his intricate black-and-white line drawings — a child’s swollen face against a pillow, blood streaming from his nose; hands gently holding a girl’s lifeless head — tell the incomprehensible stories of loss, pain and destruction that words cannot describe, that only the body understands.

“It’s a tool that means resisting oblivion, documenting history,” Al Naqqa says of his art.

A digital line drawing by Osama Husein Al Naqqa.

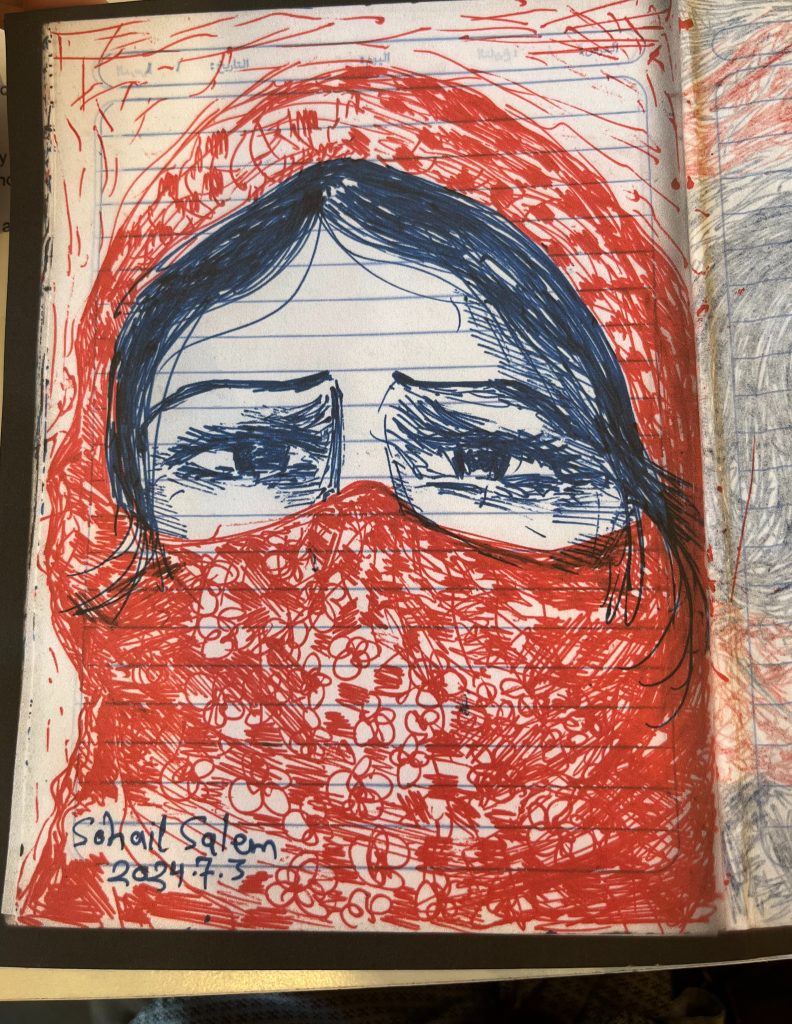

In a heartfelt letter titled “Message to friends,” artist Sohail Salem explains that he’s alive, but his “friends, relatives and neighbors have disappeared,” and “Beautiful Gaza has been destroyed.” He tells how his art has been reduced to pen-ink sketches in a student notebook: A woman brushes her hair in a mirror that reflects not her face, but a bombed-out mosque. A photographer with a press helmet photographs the moaning faces of the dead. “The idea of drawing seemed absurd,” Salem writes. “What could I draw in such conditions, and why?”

Al Naqqa’s work has reached far beyond Gaza’s borders, with exhibitions in Bahrain, Mexico, Italy, Canada and France. Salem has held residencies in Amman, Geneva, and Paris. The art has broken the siege its homeland has been under for a generation, something its creators cannot do. Many of the artists featured in the Biennale remain in the enclave, continuing their work among the destruction as best they can. The question of how such works can be displayed worldwide thus becomes one of the exhibit’s key features. Viewers will notice an ephemeral quality— Salem’s sketchbook, recreated via a series of imperfect photocopies. Or Al Naqqa’s digital line sketches, drawn on his phone between bombardments. The Biennale’s organizers, a collective based in the West Bank called the Forbidden Museum of Jabal Al Risan, prefer to describe the works not as reproductions but as “in a displaced form,” or ex situ, a Latin phrase that refers to the conservation of an endangered species outside its natural habitat. With its pavilions fanning out across the globe, the Gaza Biennale is itself in a perpetual state of displacement; its artists are under siege in Gaza while digitized and photocopied renditions of their works carry their cries far and wide.

A sketch from Sohail Salem’s notebook.

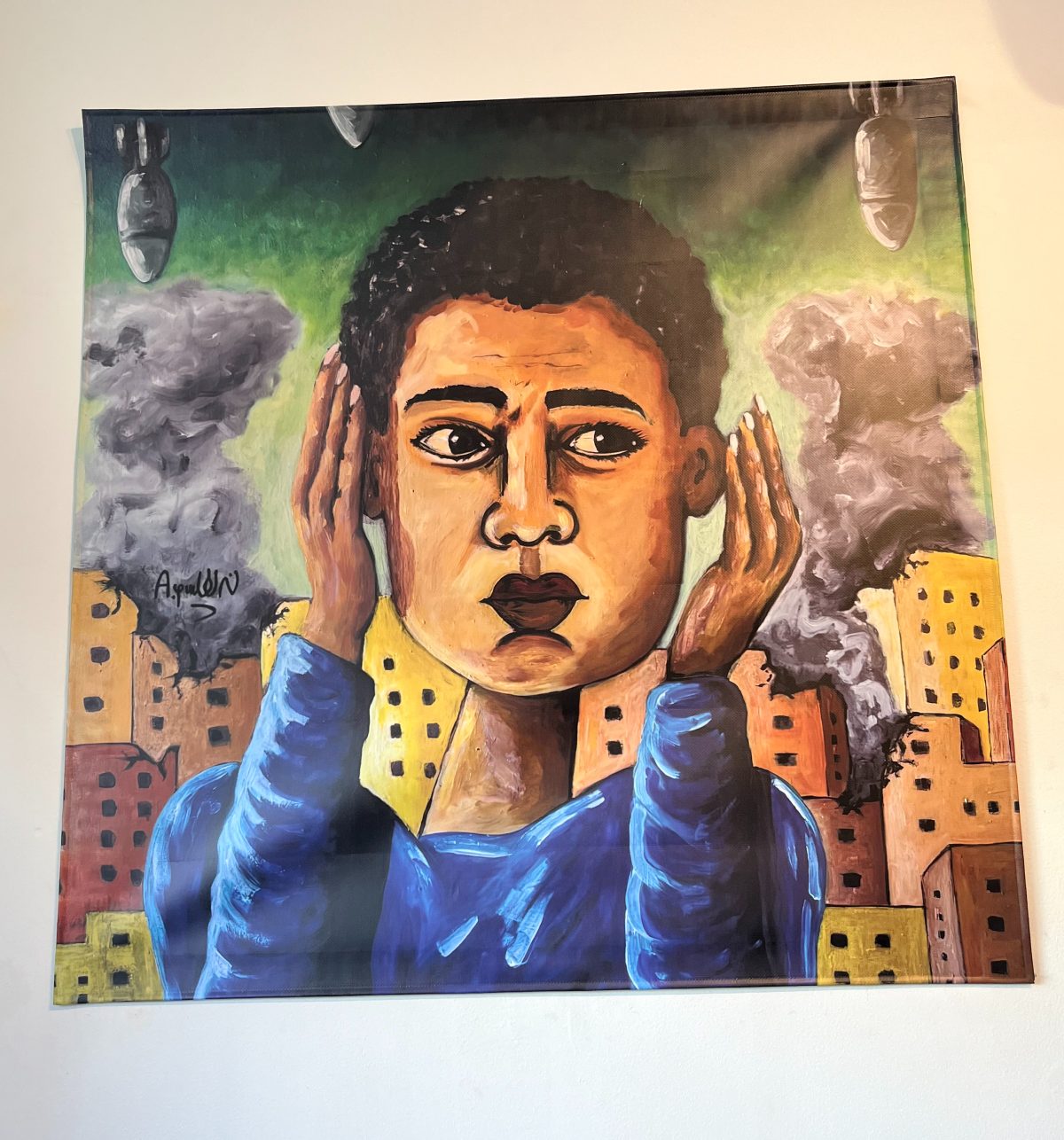

Also on display at the Biennale is the vibrant work of Murad Al-Assar, who grew up in Gaza’s Deir al-Balah refugee camp. To Al-Assar, displacement is a fact of life, as he explains in a film on view at the Biennale. His parents had lived in refugee camps, as had his grandparents, first after the 1948 dispossession of Palestinian land by Israeli forces during the Arab-Israeli War, then again during the 1967 Six-Day War. The universe inside these tent cities, where countless tragedies and microdramas unfold daily, is the subject of Al-Assar’s paintings. A child struggles to carry jugs of water that are bigger than him. A wide-eyed boy covers his ears as bombs rain down from above. Despite the desperation they depict, the paintings are an affirmation of hope, proof that the Gazan spirit lives on among the corpses and rubble.

“As an artist, I stepped into the flow,” Al-Assar says in the film. “I felt an urgent need to create, to express. I wanted to send a message to the world: I’m alive in Gaza. I haven’t died yet.”