By Stella Raine Chu

On May 6, Governor Kathy Hochul announced a statewide restriction on smartphones in New York K-12 public schools. The policy makes New York the largest state to implement a ‘bell-to-bell’ ban, where unsanctioned smartphone use throughout the entire school day, including lunch and study hall periods, is strictly forbidden.

“I know our young people succeed when they’re learning and growing, not clicking and scrolling — and that’s why New York continues to lead the nation on protecting our kids in the digital age,” Hochul said in the announcement.

The new rule allows for schools to develop their own plans to store smartphones, with an allotted 13.5 million dollars in funding for storage solutions. Teachers, parents, and students are to be consulted in the makings of these rules. The policy also leaves room for exceptions for students with special or medical needs.

The ban, to be implemented in the upcoming school year, comes at a time where every student in the K-12 system is a ‘digital native,’ a term for those who grew up in the digital age of technology.

Schools across New York have already implemented their own solutions to disruptive smartphone use in classrooms. Many seem to have found their answers in Yondr, a neoprene phone-sized pouch secured with a lock that only a specialized magnet can open.

In the morning, when students enter the building, they are to put their phones away in the pouches, which are then locked by a school administrator. The students carry the pouch with them at all times, which are only unlocked at the end of the school day. The solution seems ideal—the school is not liable for phone storage, which is risky and expensive, and the students are still responsible for their phones without access to them—but it’s not foolproof.

“Kids are much smarter and more creative than anyone gives them credit for,” said Lily Wittrock, 31, who was a public school teacher in the Bronx for eight years.

She says that students will find any way around the pouch’s mechanisms, including smashing them until they break open, or using burner phones to seal away while they keep their real phone to use during the day. Online, neodymium magnets, the only ones strong enough to open the pouches, are bought by those desperate enough. The magnets, like contraband, are passed around the students as they take turns unlocking their phones.

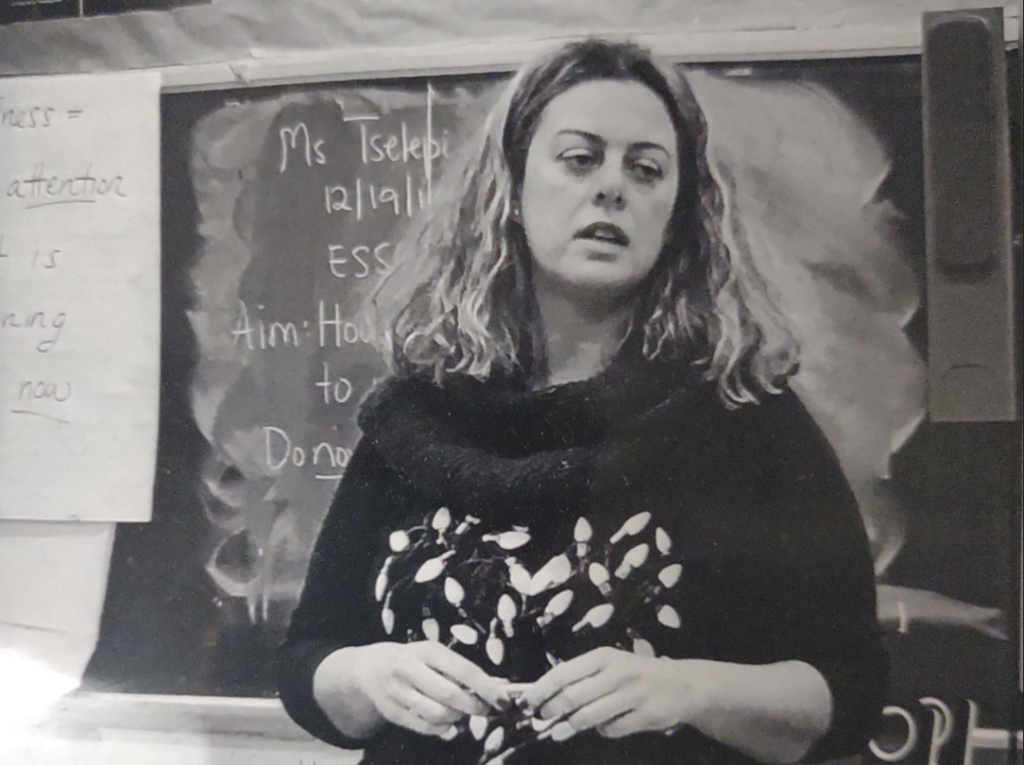

Alexandra Tselepis teaching her students, 2018. Courtesy of Alexandra Tselepis.

“They’re the perfect addicts,” said Wittrock. A 2023 Pew Research Center study found that one in five teenagers say that they are on Youtube or TikTok ‘almost constantly,’ with about half of teens using Snapchat or Instagram daily.

While fears of smartphone addiction and its effects on adolescent mental health have plagued headlines for the past decade, a bigger problem is starting to emerge: students are falling behind.

Scores of teachers have taken to sites like Instagram and TikTok, filming in their cars with their heads in their hands, sometimes even in tears, that their elementary or middle school students cannot read or write at their expected grade level.

Alexandra Tselepis, 48, has been a teacher at Atlas High School, formerly Newcomers High School, in Long Island City for 20 years. She says that her students, some of which are learning English as a second language, will write their essays as if they were texting.

“The word ‘love’ is not spelled ‘L-U-V,’ and the word ‘you’ is not just the letter ‘U,” she said. She believes that students’ overreliance on tools like Google Translate and autocorrect have dulled their spelling and grammar skills in essay and composition writing.

“They don’t think for themselves critically,” she said. “They just go on Google, get two, three, four ideas and just put them on paper. Most of the time they don’t even read what they copy and they hand it in.”

A mix of students’ dependence on technology and the COVID-19 pandemic have slowed learning among students. In 2022, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) found that only a third of the nation’s fourth graders performed at or above proficient reading levels expected of the age bracket. The same assessment found that even less eighth graders met that criteria.

The smartphone ban, while imperfect and certainly needs time to fully implement, might just be a step in the right direction—given that other problems in the classroom are resolved.

Tselepis says that, in her classroom, there are often issues with the technology, such as tablets, laptops and desktops, that the school provides the students. Teachers then have no choice but to let students use their phones to get through their lessons.

“So that’s when the problems come in, because you have to walk around and you have to see and monitor what the kids are doing,” she said. Time that could be used to teach the actual lesson then goes to ensuring that students aren’t scrolling social media or playing mobile games.

A teacher’s job becomes less about teaching and more about babysitting—at least that’s how Grace Foxen, 35, felt when she was a substitute teacher for a middle school in East Harlem. The school she subbed at used Yondr pouches, but did not inform her how they worked and that they needed to be unlocked at the end of the day.

“Students were fleeing,” she said. “They broke open the pouches and threw them at me and left the room. So I left. I wasn’t in tears, but I was almost in tears.”

Behavioral problems in students when it comes to their smartphones isn’t new. Tselepis says that she even saw students experience withdrawal symptoms from being away from their phones.

“They acted out—they’re very confrontational,” she said. “And it all went back to, ‘let me use my phone. Let me unpouch my phone. Give me five minutes.’”

Smartphone addiction means that students are no longer present in the classroom. Nothing is quite as stimulating as entertaining, short-form content at the click of a button. A math lesson scratched onto a chalkboard is nothing compared to an entire world at their fingertips.

While more seasoned teachers may be more cynical about the smartphone ban, believing that students will always find a way around the rules, those that come from a generation more familiar with technology, like millennials, aren’t so quick to give up.

“Kids are really able to access information in ways they’ve never been able to before,” said Wittrock. “So many kids find pockets of communities, when maybe their families at home aren’t supportive. They can just sort of dive into something and that sustains them.” Wittrock will be teaching at a new school in downtown Manhattan this upcoming fall, where she, along with tens of thousands of other public school teachers, will face the new policy—and the reactions that’ll come with it.

While the ban may face its fair share of resistance, Foxen, an art teacher, believes that it may open the door to something that’s been missing in classrooms for years.

“The opportunity to connect your body with your mind is such a gift,” she said. “And if we can tap into that, and having no phone supports that, I’m so excited to be present and feel that with them.”

Tselepis, with more experience and an evergrowing list of stories to tell, knows that, while the ban is well-intentioned, there needs to be enthusiastic participation from both teachers and parents. For the students themselves? They have to want the change—for the better.

“There’s nothing more beautiful than growing friendships and connections and relationships with people whom you can have a conversation with face to face, whom you can experience life with,” she said. “Looking at a screen might give you easy access and quick results, but in the long run, it’s only frying your brain.”

“Take living life. Not a screen.”