Marty Raskin holds Forest Hills HS circa 1950s teacher bowls & a sample of his button & hat collection.

Retired Teacher Marty Raskin Preserves Rare Public School Artifacts

By Forest Hills Times/Queens Ledger Columnist Michael Perlman

“School days, school days; Dear old Golden Rule days; ‘Reading and ‘riting and ‘rithmetic; Taught to the tune of hick’ry stick…” are the lyrics of the historic song, “School Days,” performed by Albert Campbell in 1908, and composed by Gus Edwards and Will D. Cobb in 1907. That is the tune that emerges when stepping into retired NYC teacher Marty Raskin’s compact but significant space, devoted to NYC public school history and rare memorabilia, which dates as far back as the early 1800s.

On June 27, this columnist had the honor of visiting Raskin, a longtime collector, lecturer, and curator by passion. His collection is likely the largest and most diverse of its kind. Now a commendable effort is underway to develop a secure, temperature-controlled, and accessible spot for the P.S. Museum, but not without public feedback for a location within the five boroughs.

A portion of Marty Raskin’s rare public school collection.

Some local public schools are P.S. 175, P.S. 101, P.S. 144, P.S. 139, P.S. 174, P.S. 196, P.S. 220, P.S. 206, P.S. 303 (formerly P.S. 3 – The Little Red Schoolhouse), Stephen A. Halsey J.H.S. 157, Russell Sage J.H.S. 190, and Forest Hills High School. Behind the classical facades of these historic schools are many stories pertaining to their development, curriculums, and achievements, which await rediscovery. Whether local or citywide, artifacts from within can also bond generations of teachers, students, parents, and the greater public, as if the spirit of our ancestors walks alongside us, continuing to educate.

A revolutionary date was April 9, 1805, when the legislature passed “the Act to incorporate the (Free School) Society instituted in the city of New York, for the establishment of a free school for the education of poor children who do not belong to, or are not provided for by, any religious society.”

At 84 years young, Raskin, who was born and raised in Brooklyn, and is a 25-year Manhattan resident, is a visionary and an achiever. He began his schooling at P.S. 202 in East New York and later achieved two Masters degrees from Long Island University and CW Post. His teaching career originated at Canarsie High School in 1966, and he retired in 1989. This is where he taught business education and established work experience programs for special needs students. “I was the first member of my family to attend college. My brother is also a retired teacher, so we have it in our family,” said Raskin.

One must wonder about what motivates Raskin to pursue his unique interest. “I’ve always been a collector. In the 1970s, I taught a class, ‘The Business of Antiques,’ and for the term project, we did an antiques show.”

Pencil sharpeners & thermometers.

Between magazines, books, articles, and photos, as well as artifacts in the form of objects, Raskin estimates collecting over 1,000 museum-quality items. Among the earliest possessions are a textbook from 1807, a dunce chair from the early 1800s, and a treasure trove of memorabilia from the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s. He admits that it would prove challenging to pinpoint standout collectibles. “A collector loves everything, but the dunce chair is one, an electrical learning component is another, and my collection of New York City clocks that were in every single classroom. Any one of my things can be a highlight to me,” he said. The smallest collectibles are his large assemblage of academic and sports medals, and the largest items are a teachers’ learning desk from 1925, teachers’ reading chairs from the early 1900s, and a vintage principal’s bench. Certain larger collectibles are on permanent display at the United Federation of Teachers Headquarters at 52 Broadway in Manhattan.

Raskin’s vision is meritorious. “I want to donate the entire collection to set up a museum to honor the teachers and the teaching profession. I don’t want to break up the collection. The agreement would need to have a provision, where the person or persons that I designate to oversee the aim of the collection is followed. I am not looking to donate it, to be kept in some basement.”

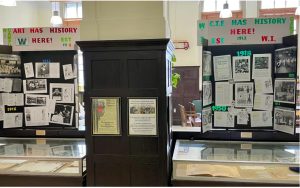

Exhibit curated by David Edelman’s students.

His Electric Automatic Instructor, which was patented in June 1885, continues to be operational. A December 23, 1886 ad in the Buffalo Daily Courier read: “Greatest Novelty of the Age! For the holidays and all time, The Electric Automatic Instructor, One of the Most Wonderful Inventions of Modern Times. Something every family in the land should have. More knowledge and information can be obtained than from hundreds of dollars’ worth of books!” It was on exhibition and for sale only by F.S. Pease’s art department at 65 and 67 Main Street. This innovation benefited children and adults. A December 3, 1893 New York Press article referenced that it consisted of a set of large cards with questions and answers laid on a board over a small battery. “A steel pin is struck through the question on one side of the card. Another pin, fastened to a string connecting with a concealed battery, is run rapidly up and down the steel pins through the answers on the other side. A bell rings when the right pin is touched. It is very mysterious and delightful to a young mind, of course. This ‘toy’ costs $5. There is also an electric launch which runs for an hour for $22.50.”

Not all educational tools of yesteryear can be deemed fully beneficial. In America and Europe, the dunce chair was used along with a dunce cap, which a student wore to demonstrate intellectual inadequacy and punishment for misbehaving. It was especially popular during the Victorian era, but was phased out due to its potential for psychological impacts.

The Public School Museum concept is already branching out. “I am incredibly thankful to Marty Raskin, who has inspired my students and I to investigate our own school’s history, and helped kickstart our exhibition with items from his personal collection,” said 43-year-old David Edelman, a Forest Hills resident who teaches social studies at the historic Washington Irving Campus High School at 40 Irving Place in Manhattan. “It is gratifying that some of my students’ favorite lessons teach students about U.S. history and government through the lens of public schooling,” he continued. The on-site exhibition commemorates the history of student life, teaching, and learning in conjunction with the school. Edelman and his students hosted DOE administrators, members of City Council, and international students.

David Edelman holds circa 1953 Washington Irving HS student attire & Marty Raskin holds circa 1958 Richmond Hill HS cheerleader uniform.

Edelman values how enthusiastic his students are when it comes to examining turn-of-the- twentieth-century artifacts, articles, and photos from the Boys & Girls Youth Police squad program, with the generosity of Raskin’s collection. He explained, “These objects not only foster student engagement, but help students draw connections to contemporary issues related to policing and programs they have participated in, such as the modern NYPD Explorers Program.”

Edelman also utilized items illustrating the Open-Air Schools movement, which was intended to combat the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 to 1920. “This helped my students draw historical connections to their experiences during the Covid pandemic. They analyzed items from Marty’s collection, and many referenced them when they crafted proposals to New York City Council,” he said. A scavenger hunt is among the interactive events that Edelman coordinates, where his students take the lead and focus on the history of their school. He explained, “They pursue it collaboratively, such as when school groups from Germany visited, or when elementary and high school students participate. I may ask them to find three examples of civic engagement from the past, and reflect upon how it compares to what they accomplished in school. Also, to find examples of vocational training, and explain how it compares to what students are pursuing today.”

Edelman admires how Raskin is a people’s person, as much as a collector, who loves interacting with students and teachers across generational divides. “That’s also what is so amazing about his collection and school history. It establishes an ability to connect people, young and old, around their school-related experiences,” he said.

Edelman became aware of the collection around 12 years ago, and Raskin donated certain collectibles with an intent of benefiting his students. “David is one of the true educators who appreciates and understands what we are looking to do,” he said.

Raskin coordinated exhibitions and lectures at retirement communities, The City Reliquary Museum & Civic Organization, principals’ and teachers’ unions, and for the American Federation of Teachers in Pittsburgh and Boston. When an event focused on retired teachers, his passion for preservation unfolded before his eyes. “I brought out a Delaney book, and some teachers started crying and said, ‘I haven’t seen these in 40 years.’ This is why I want to preserve these artifacts.” A museumgoer would learn that this book, invented by Edward C. Delaney, features Delaney cards, which are placed in slots to keep track of grades and attendance, and consists of a seating layout.

Ornate bronze classroom Doorknob collection.

Another much admired collectible that attendees enjoy discussing are intricate bronze doorknobs from classrooms, which feature scrollwork and typography. A most popular model is oval and reads, “Public School ~ City of New York.” This architectural hardware began appearing in schools around the early 1900s and was produced by Sargent and Corbin. Another model with the same design was produced for the City of Reading, and a Reading variation features a teacher and a student reading in front of a globe. Some knobs offer the unique overlay of typography in the form of school acronyms, such as for Girls’ High School in Brooklyn.

Every collectible bears the potential to communicate loads of stories. “I have a large amount of teacher files, which show what teachers went through, starting in 1920. It makes me very proud that I can follow teachers to see what it was like when they were doing their job,” said Raskin, who cited concerns and problems, such as what they may have experienced with their principal. “Nothing has changed,” he chuckled. “A lot of the same things that happened in the 1920s, are happening in the 2020s.”

Sample classroom necessities including inkwell supply.

Washington Irving H.S. issues an annual State of the Union report, where teachers from various departments include accomplishments and challenges. On a related note, Edelman came across a vintage civic department document, and shared a scenario that bonds the generations. It was addressed to Mabel Skinner, Chairman, Civics Department, Washington Irving H.S. on June 15, 1936: “My dear Miss, I thank you for letting me know by a letter how poor I was in Civics. Miss, I would like you to know that I came from Italy not so long ago and sometime till now I can’t understand some words. I will try my best to improve in my work. Thank you for your kind letter you gave me.” Edelman explained, “Challenges that students faced 100 years ago are the same, although the historical narrative is different. Students can learn American history through the eyes of students who were sitting in the very same seats, and discover their legacy.”

“I made influential people aware of my collection in my quest to find a permanent home,” said Raskin. A highlight was when Debbie Schaefer-Jacobs, Cultural and Community Life Curator of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History visited, and spent over 6 hours viewing his collection. He rehashed being told, “Marty, this collection belongs in New York City. There is nothing like this in the U.S.” He continued, “You have a museum for sex, chocolate, and transportation, but there is no large museum to honor education.”

Food from children’s and teacher’s cafeteria and home products.

“When I am not collecting, my joys in life are my grandchild, spending time at home, going to the gym, and traveling,” said Raskin. He offered advice to younger generations of collectors, who may have an interest in opening a museum or gallery. “Enjoy your quest. At some point, you may come to the realization that you want to go further with your collection, such as donating it. These are only things, and we own them for a small amount of time. As you get older, think of how you want to pass along your collection.”

A solid education entails teaching not only American and global history, but local history, which can most effectively be accomplished through preserving educational artifacts. By students and visitors observing and selectively touching objects and photos, a “living museum” comes to fruition. There is a deeper foundation than only reading a textbook or an e-book, but some schools have unfortunately discarded memorabilia. Raskin, who hopes to reverse the needless throwaway culture by preserving what remains, explained, “There’s so much good stuff that is still around. When Evander Childs High School in the Bronx closed, they shut the library. When they reopened it into five schools, they didn’t want anything that said ‘Evander Childs.’ They threw everything out. When I was at Jamaica High School, they said that they didn’t want to know about this stuff.”

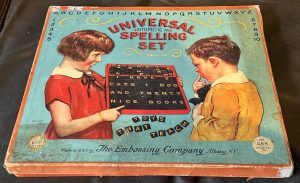

Educational set, circa 1940s.

Typically, younger generations think “less is more,” according to Raskin. Edelman then stated, “When you show it to school-age students, they’re fascinated by it.” Raskin added, “Last year, I was invited to do a 100-year anniversary of a public school in Brooklyn, and when I showed the kids my writing instruments – inkwells and fountain pens, and how you work a telephone (antique model), they were fascinated.” Therefore, education is key.

Raskin, who owns over 60 albums of ephemera, shared a related account of the role that NYC public schools played during WWII. “On December 7, 1941, the night before President Franklin Delano Roosevelt made his speech (“Day of Infamy”) taking us into war, all NYC public high school principals were told that on the following morning at 9:00, bring your seniors down to the auditorium, and FDR will make a major announcement. At DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, students came into the auditorium, and the principal spoke. There was a big radio (predating television) and FDR made a speech that we’re going to war. Then the back doors of the auditorium opened. In the lobby, recruitment stations were set up. Within the first three months, 400 students signed up.” His collection also documents the schools’ roles in fundraising and personal letters. At certain vocational schools, shops were retrofitted to produce necessities for wartime, and some schools were open 24 hours. “There was such a great feeling of nationalism,” he continued.

Left, 1849, All pieces appear in work written by pupils in the ward for public schools of the City of NY, as part of their exercises while pursuing their studies – Short stories & sonnets.

When the P.S. Museum materializes, various forms of interactivity will be part of the mission, consisting of not only the permanent collection, but exhibitions with guest-speaking opportunities. “When I prepare a packet to tell attendees about education, I use a model in Los Angeles, where they have a small museum of learning and teaching. They have speakers and classrooms where groups come into. It is multifaceted,” said Raskin.

To donate collectibles to Marty Raskin or suggest accessible and secure locations for the P.S. Museum, please email memorabuti@gmail.com, davidedelman@gmail.com, & mperlman@queensledger.com. Also, bookmark www.thepsmuseum.org for updates.

Ornate personalized school gifts.

Student at Brooklyn HS for Specialty Trades circa 1930s – 1940s, Vintage typewriter & Barrett adding machine from Brooklyn elementary school office.

1927 prom giveaway.

1940s school crossing guard, 1920s metal sign, mid-1800s dunce chair, & Electric Automatic Instructor.

Old-world bells & classroom.