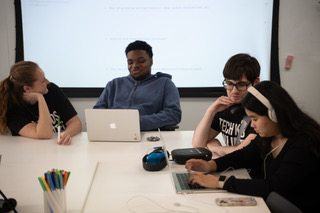

Students work on digital projects during a workshop. Photo courtesy of Tech Kids Unlimited

By Jack Delaney | jdelaney@queensledger.com

As with many great ideas, Beth Rosenberg conceived of Tech Kids Unlimited through equal parts necessity and chance.

The year was 2009, and Rosenberg was working as a special needs consultant at a school in Manhattan, building upon a career at the Guggenheim and in museum education writ large. Yet she was having difficulty finding resources for her own neurodiverse son, Jack, a then 10-year-old who loved technology.

Taking matters into her own hands, Rosenberg put together one week of programming for 12 kids — a crash course in stop motion animation. As she recalls now, the response was both immediate and unambiguous: “The parents said, ‘Well, can we have more?’” There was a need, clearly, and Rosenberg set about meeting it through a fresh slate of classes.

Today, Tech Kids Unlimited (TKU) — whose mission is to “empower neurodivergent youth through technology education and career preparation” — has grown to serve 542 students, encompassing not only New Yorkers but online participants from 12 additional states. Part of that expansion was made possible by a windfall in 2013, after Rosenberg started a job as an adjunct professor at NYU Tandon School of Engineering in Downtown Brooklyn. Her boss, curious about her workshops, asked whether she would bring the burgeoning program to the college.

Until then, the scrappy prototype for TKU had largely been a function of Rosenberg’s force of will — for four years, she pulled together flyers and booked rooms wherever she had an affiliation, typically Pace University or the JCC. But that conversation at NYU changed the equation by offering a long-term space in which to scale, and it spurred Rosenberg to register TKU as a nonprofit in 2014. “From that point on, we had a home base,” she said. “I had access to classrooms in the summer and in the evening and on Fridays, so we could expand the program.”

TKU, still housed within NYU Tandon, now boasts a suite of options. Interested parents of children and young adults can choose from 14 distinct programs that fall within two general tracks: “tech knowledge” and “career ladder.” While the organization was formed around the former, Rosenberg said that the latter has become her main concern. “We’re graduating more and more students from high school and even community college,” she said. “But the work learning piece, the getting a job piece, is virtually not there.”

TKU’s students come from a wide range of backgrounds, both in terms of age (7 to 21) and abilities. But to pick one example, a 2017 census by Drexel University of Americans with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) found that only 38% of respondents were engaged in paid jobs, whether full or part-time, highlighting the barriers those with learning disabilities face in finding employment.

For her part, Rosenberg believes this gap is exacerbated by disinvestment and stigma, and can be closed. “You don’t really see kids with special needs working unless they’re shelving vitamins at the grocery store or at Target,” she said. “I’m sick of it, because our kids are capable of so much more. But the world doesn’t see that.”

One of the nonprofit’s flagship programs is the TKU Digital Agency, which allows students to build skills by designing social media posts and other digital products for big-name partner companies. AMC, a recent client, used students’ creations to promote its show “Orphan Black: Echoes.“ Those posts received high praise: “It was nice to be able to share our knowledge with individuals who truly appreciate it,” AMC reps wrote, “and we were very impressed by all the ideas, work, and execution.”

Later this month, TKU students will be contributing to the fourth installment of the Marvels of Media Festival at the Museum of the Mov- ing Image in Queens, which runs from March 27 to March 29. The free event caps off a year-round initiative by the museum to “showcase, celebrate, and support autistic media- makers of all ages and skill sets,” and will feature VR experiences, video games, and film screenings followed by panel discussions.

Tonya Blazio was a graduate student at NYU when she found TKU through a newsletter. Her son Tate, who has IDD, had always been creative — to this day, he brings the objects he crafts into class to show everybody — but he fell in love with stop motion at a workshop, and has been obsessed ever since. More than that, Blazio said, her son discovered a safe space to learn alongside other kids: “Just seeing the improvement in my son’s work, his social skills, his ability to better communicate and understand how technology is avail- able to help him — it’s been really tremendous.”

That sense of support and be- longing extends beyond the students themselves, Blazio noted. “It takes a village to raise a child,” she said. “When parents realize, ‘Oh, I’m actually not in this all by myself,’ there’s all this information that you can share, and that’s been quite helpful for me.”

Though TKU’s pedagogy has evolved since 2009, it has kept its original emphasis on small class sizes. (“If it was good enough for the Queen of England,” Rosenberg said, referring to personalized tutors, “it should be good enough for our kids.”) Once the organization attained non- profit status in 2014, it indexed heavily into project-based learning and design thinking, incorporating those principles throughout its curriculum. Another guiding paradigm is the special needs-oriented Universal Design for Learning, which encourages teachers to meet students where they are by “offering more than one way to access information.”

Nearly eight million students across America received services for disabilities in 2022-2023, the last school year for which data is available, accounting for roughly 15% of public schoolers. New York City alone is home to 200,000 students with special needs, though that moniker, which applies to 19% of the student population, casts a wide net; about 80,000 kids had learning disabilities, and just over 20,000 had ASD.

With April around the corner, Rosenberg and her team are spreading the word about their summer workshops. Each week is devoted to a different discipline, such as game design or video editing, and timing is flexible: parents can drop their kids off for either half or full days, and can sign up for whichever weeks they need. (You can learn more at techkidsunlimited.org.)

“These kids are interesting, quirky, fabulous — they’re, you know, kids,” said Rosenberg. “[My son] went through TKU for 10 years: he learned time management, how to collaborate, how to take constructive criticism. And he learned how to advocate for himself.”

How is Jack faring, more than a decade after his passion sparked Rosenberg’s early efforts to ensure kids with special needs flourish? “I went out to dinner with all my SPED mom friends in December,” she said proudly, “and he was the only kid who was working.” Her son received an associate’s degree from Pace, which has a disability program, and he now works part-time as an operations assistant at the Shirley Ananias School, a special ed school in downtown Manhattan.

Blazio has seen a similar maturation in Tate, who she said became more independent thanks to TKU’s programs. “At one point, they don’t want you to leave them,” she said. “And then the next year or so, they’re like, “‘See you, mom!’”