Courtesy Jordan L. Smith/The Pie Shops Collection

By MOHAMED FARGHALY

mfarghaly@queensledger.com

From the moment Mary Vavruska was a child, the towering spires of the New York State Pavilion loomed large in her imagination. Growing up in Queens, she had a front-row seat to the iconic structure that stood as the centerpiece of the 1964 World’s Fair. It wasn’t just a landmark to her—it was the spark of a lifelong passion, a symbol of both personal history and her connection to the city’s architectural legacy.

Vavruska’s fascination with the pavilion started early. As a child, she would visit her grandparents’ apartment in Jackson Heights, which offered a panoramic view of Flushing Meadows-Corona Park and the pavilion itself. Her grandparents, who attended the World’s Fair, often shared stories about the event, deepening Vavruska’s connection to the place.

“A key piece of information in this story is that my grandparents are from Jackson Heights and growing up I would visit their apartment, and from their window, they had a great view of Flushing Meadow Park, and I could see the Unisphere in the New York State Pavilion from their window,” Vavruska said. “They attended the World’s Fair, and I grew up hearing stories about it, and plus, my parents explained the history of it to me.”

But the spark that would fuel her passion for restoring the pavilion came during the 50th anniversary celebration of the World’s Fair.

“I think the point where I really felt like this passion started burning inside me was when they had the 50th anniversary event for the 1964 World’s Fair, and they opened up the New York State Pavilion,” Vavruska said. “I went with my friend Theo, and we waited in this like crazy long line to go inside the New York State Pavilion. I was so excited to see something I heard about my entire life, and finally I could actually see the inside. Going in, it was like, so cathartic, but at the same time, it was actually really heartbreaking to see that, like the state that it was in on the inside.”

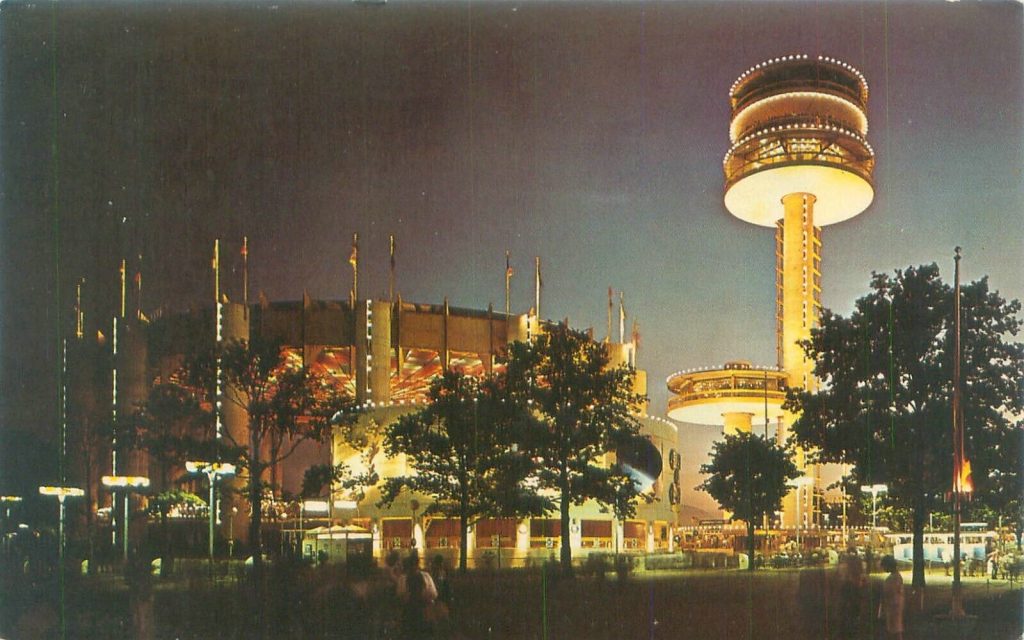

The New York State Pavilion, located in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens was originally built for the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Designed by celebrated architects Philip Johnson and Richard Foster, with structural engineering by Lev Zetlin, the pavilion consists of three distinctive reinforced concrete-and-steel structures: the Tent of Tomorrow, three observation towers, and the Theaterama. The Tent of Tomorrow is a massive elliptical structure, measuring 250 by 350 feet, with a cable suspension roof that was designed to resemble the future of architecture. Beneath its soaring roof lies a terrazzo map of New York State, which once served as a landmark feature. The three observation towers, with the tallest standing at 226 feet, were intended to offer panoramic views of the fairgrounds, while the Theaterama, a drum-shaped building, functioned as a space for films and exhibits. Designed to be one of the tallest and most striking pavilions at the World’s Fair, it stood as a symbol of modernity and innovation.

After the fair, the pavilion’s structures were repurposed for a variety of uses, including concerts, exhibitions, and roller rinks, but by the late 20th century, they had fallen into disrepair. The once-vibrant Tent of Tomorrow and observation towers were abandoned and left to deteriorate, with parts of the terrazzo map damaged and the towers falling into ruin. Despite the decline, the pavilion has been the focus of several restoration efforts, culminating in its addition to the National Register of Historic Places in 2009. Recent preservation work has focused on stabilizing the structures, including repainting the Tent of Tomorrow in its iconic yellow color in 2015, repairing the terrazzo map, and updating the observation towers with new lighting and structural enhancements.

Vavruska’s connection to the pavilion took on a deeper meaning. It wasn’t just about preserving a building—it was about safeguarding a piece of history that had shaped her own identity.

“I think after seeing it like that, it went from kind of having a passing interest in the World’s Fair in its history to wanting to really get involved in preserving it for the future and giving other people the opportunity to enjoy its history the way I have,” Vavruska said.

Her childhood curiosity for structures, combined with an interest in engineering, led her to pursue a career in structural engineering.

“I’m a structural engineer now and growing up in a city surrounded by amazing buildings, bridges, and incredible structures sparked my curiosity,” Vavruska said. “Even though I didn’t know what civil engineering was at the time, I was always fascinated by how these structures came to be and how they worked. Structural engineering, which is a branch of civil engineering, felt like the perfect fit for my interests. As I continued to learn about structures, I developed a strong passion for historic preservation. I realized that through my career, I could make a real difference. That’s when I knew I wanted to get involved with projects like this one, to help preserve and protect these important historical landmarks.”

Her professional journey led her to T.Y Lin International, where she recently joined a team dedicated to the preservation of historic structures. As an entry-level structural engineer, Vavruska found herself in the perfect place to pursue her passion for the pavilion.

Today, Vavruska plays a key role in the ongoing restoration of the pavilion. Her team is focused on making the structure safe for future generations, despite the challenges that come with such an ambitious project.

“It seems like it’s kind of a never-ending project, and you know, it’s slow paced, and there’s limited funding for it,” Vavruska said. “Ultimately, it’s not number one on the priority list, but they’re trying to fix it up to, at least to a point right now where it’s not a safety hazard.”

Though the restoration is still in its early phases, Vavruska envisions a future where the pavilion is not just safe but open to the public once again.

“I think the ultimate goal from everything I’ve heard over the years is they want to have it be able to be used by the public in some form eventually,” Vavruska said.

The pavilion, which has long been a symbol of New York’s bold vision for the future, also faces challenges of public perception. For many, it’s just another relic of a bygone era, but for Vavruska, it represents so much more.

Vavruska’s mission isn’t just about bricks and mortar—it’s about preserving the soul of a place that has left a mark on the community and on her own life.

As she works on the restoration, Vavruska’s thoughts often turn to the pavilion’s original architects, who never could have imagined their creation would still stand 60 years later. “I’d love to know if they ever thought their design would last this long,” she said. “What did they envision for it after the fair?”

With each step in the restoration process, Vavruska feels she’s getting closer to fulfilling the dream that began when she first looked out her grandparents’ window so many years ago. For her, the pavilion isn’t just a project—it’s the story of a lifelong connection to a place she’s determined to preserve for generations to come.

“Queens is the most diverse place in the world and the World’s Fair perfectly captures that, I mean the world literally came to Queens twice, in the ’30s and ’60s,” Vavruska said. “While some of the futuristic visions from the Fair may seem silly or unrealistic now, there’s something beautiful about that hopeful, rose-colored view of the future. In times like these, when things can feel uncertain, we could use more of that positivity. I think it’s important to appreciate the smaller, often unappreciated little wonderful pockets of history in our city. I think there’s something really cool about remembering the seemingly less important ones and keeping their stories going as much as the other landmarks of the city.”