By Michael Perlman

mperlman@queensledger.com

There is a good chance that you mailed a postcard to family and friends, but may not realize that picture postcards date to 1893, and the majority, where a good percentage feature handwritten messages and vintage stamps, still exist. Deltiology is the collection and study of postcards, which derives from “deltion,” the Greek term for a writing tablet or letter. Therefore, a deltiologist references a postcard collector.

Forest Hills and Rego Park advertising postcards were once available for free at local restaurants, but today can sell anywhere from $10 to $50. Facades and interiors were often photographed from a unique perspective in postcards, complementing their architectural details and artistry, which extended a warm welcome to patrons.

Early 20th Century postcards featured black and white printed photos that were hand-colored and often seemed true to life. They were followed by linen-era color postcards beginning in the 1930s, followed by natural color chrome postcards as of the 1950s.

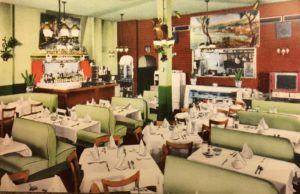

Mama Sorrento’s

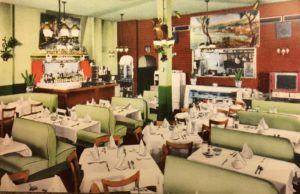

A chrome postcard, published by Adchrome Pdts. Corp. of 509 Madison Ave., read, “To make dining out a real pleasure, be sure to visit Mama Sorrento’s.” Mama Sorrento, a most distinguished Italian restaurant and pizzeria, was situated at 107-02 Queens Blvd., along a retail strip completed in 1947, facing MacDonald Park.

Beyond a well-appointed Colonial façade, it featured cozy green booths, tables, and high ceilings, along with scenic artwork, a view of the kitchen, and a bar area. Deco green walls were offset by a brick wall. This popular restaurant served genuine Italian dishes that were recognized by patrons for their wonderful presentations. Accommodations were made for all social functions, and air-conditioning and free parking were additional attractions.

Joan Rizzi was a local legend, better known as “Mama Sorrento,” who would prepare traditional Neapolitan family dishes, making the restaurant a Queens favorite. She told The Long Island Star-Journal in May 1961, “cooking is an art in my family, and the policy that we have is to satisfy the people who come into our restaurant for the finest in Italian-American dishes.” One signature dish was Chicken Rollatini alla Parisienne.

This is also where actor, comedian, and voice-over artist Marty Ingels once had his signed headshot on display, likely prior to achieving stardom. This notable spot was a phone call away at Virginia 6-9277, where the postcard features a long-forgotten vintage prefix.

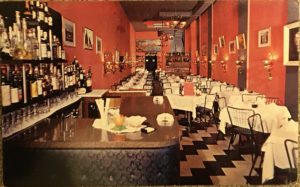

Tutto Bene Restaurant

Some postcards feature the evolution of restaurants—if you are fortunate enough to find them.

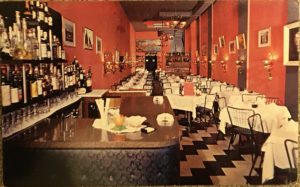

Such is the case with the chrome postcards of French Italian cuisine establishment Chez Pierre at 110-50 Queens Blvd., which opened around the early 1940s, and was later the site of Tutto Bene Restaurant, an Italian classic cuisine spot, circa the late 1960s. Both restaurants featured elegant murals, which were a mainstay of restaurants that made patrons feel as if they were on a getaway for the evening.

Checkered tablecloths in one restaurant, eventually made their way to double red and white tablecloths in another, hence the eras. The latter business featured warm wood-paneled walls and elegantly framed artwork, with small ornate chandeliers. “Tutto Bene” translates as “everything good,” and among the patron favorites were Lobster Fra Diavolo and Assortimento Tutto Bene.

La Stella

Several Italian restaurants were documented in postcards. La Stella, under the management of “The Taliercio Bros.” Joseph and Jack, was at 102-11 Queens Boulevard and featured fine Italian cuisine, wine, and liquors.

The chrome postcard displays its ambiance, consisting of orange walls, high ceilings, chandeliers and sconces, traditional Italian picture frames, and white tablecloths. The zig-zag patterned floor added much character. The angular art deco storefront featured classic illuminated script signage.

Aside from its popular menu, this is the site of the notorious September 1966 luncheon that resulted in the arrest of 13 top members of organized crime, which The New York Times called “Little Apalachin.”

Another chrome postcard featured Monte’s, a fine Italian restaurant and pizzeria at 71-51 Yellowstone Blvd. It offered home delivery and parking in the rear and was advertised as being 3 blocks from Parker Towers.

Monte’s

Looking into the restaurant, a curtained window made it resemble a showroom, and tall candles with ornate holders in each booth added to its elegance. A recessed ceiling with a chandelier, a checkered floor, and an Italian wall sketch also contributed to its mood. This restaurant would later become the cherished Da’ Silvana.

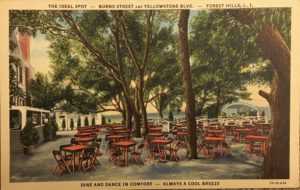

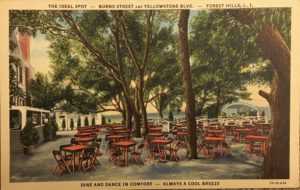

A linen postcard features the Ideal Spot on Burns Street and Yellowstone Boulevard, where patrons would “dine and dance in comfort” near a bandshell where there was “always a cool breeze” under the trees. It also featured a beer garden at 66-20 Thornton Pl., and an early ad read, “a hard place to find, but worth the effort.”

In April 1938, a license was issued to the Ideal Spot to sell beer, wine, and liquor. Living up to its name, patrons would sit at tables with checkered tablecloths under a tree canopy of Maples, where they could be acquainted with nature and keep cool under a starlit summer’s night. Open year-round, patrons could also dine and dance nightly, and games were coordinated.

Community functions included the Kew-Forest Kennel Club’s all-breed match show in 1938 and the Annual Dinner Dance and Revue of the Forest Hills Homeowners Association in January 1942.

The Ideal Spot

The jazz scene consisted of regulars Art Hodes on piano, Rod Cless on clarinet, and Joe Grausso on drums. Bill Reid’s Dixieland Band also took the stage. In 1940, patrons welcomed a new air-cooled room, where the seating capacity increased to 500, with an extra-large indoor dancefloor.

In its early days of operation, the family business consisted of Terry, Anne, Ernie, and Pop Nuerge, who helped define the neighborhood’s culture.

Patrons often walked or took their cars to the Ideal Spot, but during World War II, the clientele began to decrease due to gas rationing and the ban on pleasure driving. Thanks to the creative management in 1943, patrons rode safely in a covered wagon, which would meet at the subway stop every hour on the hour and depart from the Ideal Spot at half-hour intervals.

The tree bark-inspired menu consisted of a canapé of anchovies or a fruit cocktail for 25 cents and Soup du Jour for 20 cents. “Blue plates a L’Ideal” offered choices such as a sirloin steak for $1.25. For a quarter, patrons could order a cold sandwich of Limburger cheese or liverwurst, and for 50 cents, order a caviar sandwich. The Ideal Spot closed in 1962, and then the property accommodated a series of Yeshivas.

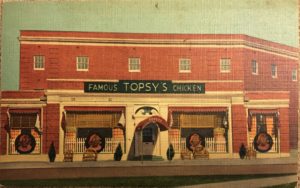

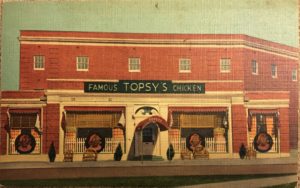

Topsy’s

Topsy’s Cabin Fried Chicken, also known as Topsy’s Chicken, a southern-style culinary landmark that also served corn fritters among its most popular options, opened in 1937 in a one-story Colonial building at 112-01 Queens Blvd. in Forest Hills, which later became a two-story Colonial building. The Topsy’s façade was initially depicted in a linen-era postcard.

The Topsy’s slogan was “Eat It With Your Fingers.” A Topsy’s billboard once caught the eye of community residents and read “m-m-m one block ahead” and also stated “famous for chicken,” with a tempting plate. Examining postcards, often makes one conduct further research. In this case, it was replaced by Seymour Kaye’s in 1971, which specialized in Jewish dining. In 1989, the site became The Pinnacle, as we know it.

Diners once dotted the tri-state area. One can see from a George Hollis Diner linen Colourpicture postcard a classic example of art deco, which was a highlight of many sites, thanks to the influence of the nearby 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows. Mr. Hollis was at your service at this freestanding railway car-inspired diner, which was in existence potentially into the late 1950s. It featured striking curved corners of glass blocks and sleek horizontal and vertical details.

The George Hollis Diner

It was located at 109-23 World’s Fair Blvd., which was temporarily renamed Horace Harding Boulevard, and was near 108th Street. The postcard read, “In the Shadow of the World’s Fair” and “dine here and enjoy the finest food in a rare atmosphere of beauty and distinction. Counter and booth service. Always open.” Numerous fairgoers’ palates were enticed! The Fair’s symbolic spire-like Trylon monument was evident in its path.

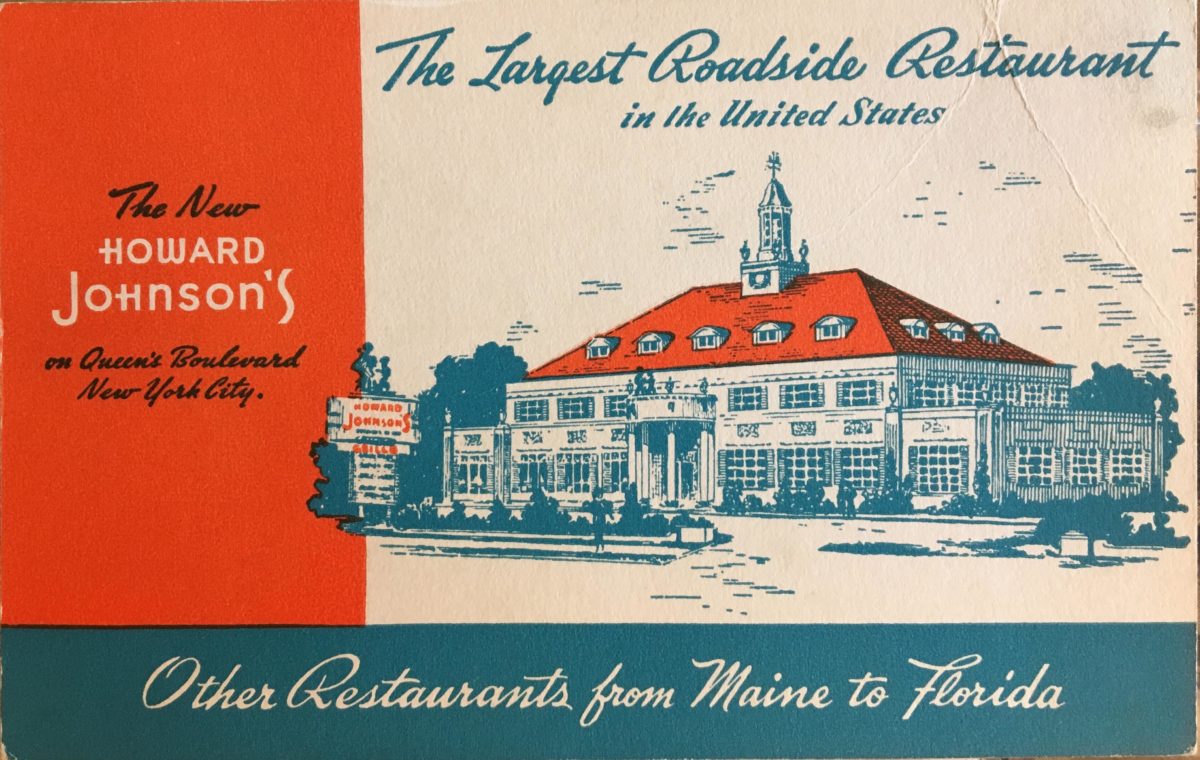

Rego Park postcards are a novelty since far fewer views exist than Forest Hills postcards. One features a colorful sketch of Howard Johnson’s at 95-25 Queens Blvd., which was advertised as “the largest roadside restaurant in the United States,” coincided with the 1939 World’s Fair and won first prize from the Queens Chamber of Commerce.

It sat 1,000 patrons. The Georgian Colonial mansion-like façade featured sculptures, ornamental cast stone, pilasters, a portico, dormers, shutters, and terraces, and was topped off with a cupola. A freestanding art deco sign boasted 28 ice cream flavors such as chocolate chip and burgundy cherry ice cream, as well as a grille and cocktail lounge. Weddings were held in the “Colonial Room” and “Empire Room.”

Regal appointments included crystal chandeliers, a winding grand staircase, and murals by the famed Andre Durenceau. The 1939 World’s Fair’s esteemed seafood chef Pierre Franey was on-site. It is also where chef Jacques Pépin worked and was later the recipient of an Emmy Award for Lifetime Achievement. In 1974, this unofficial landmark was demolished, but it is forever etched in the heart of many New Yorkers.