The apartment complex where the Sajid family received a notice to evict.

By Iryna Shkurhan | ishkurhan@queensledger.com

After years of moving around between Pakistan, Canada and Texas, Sumra Sajid and her family were finally able to call a Fresh Meadows apartment home for the past 13 years.

Like many families, they fell on hard financial times during the pandemic. Sajid Khan, her father and the sole provider for the family of eight, could no longer work as a taxi driver due to a lack of demand and safety concerns. For months their rent went unpaid, and their arrears accumulated to over ten thousand dollars.

Word of the Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP), a federal government program to support housing stability during the pandemic, felt like a lifeline. They applied immediately with hopes that relief and security would replace the intrusive thoughts that told them they could end up homeless.

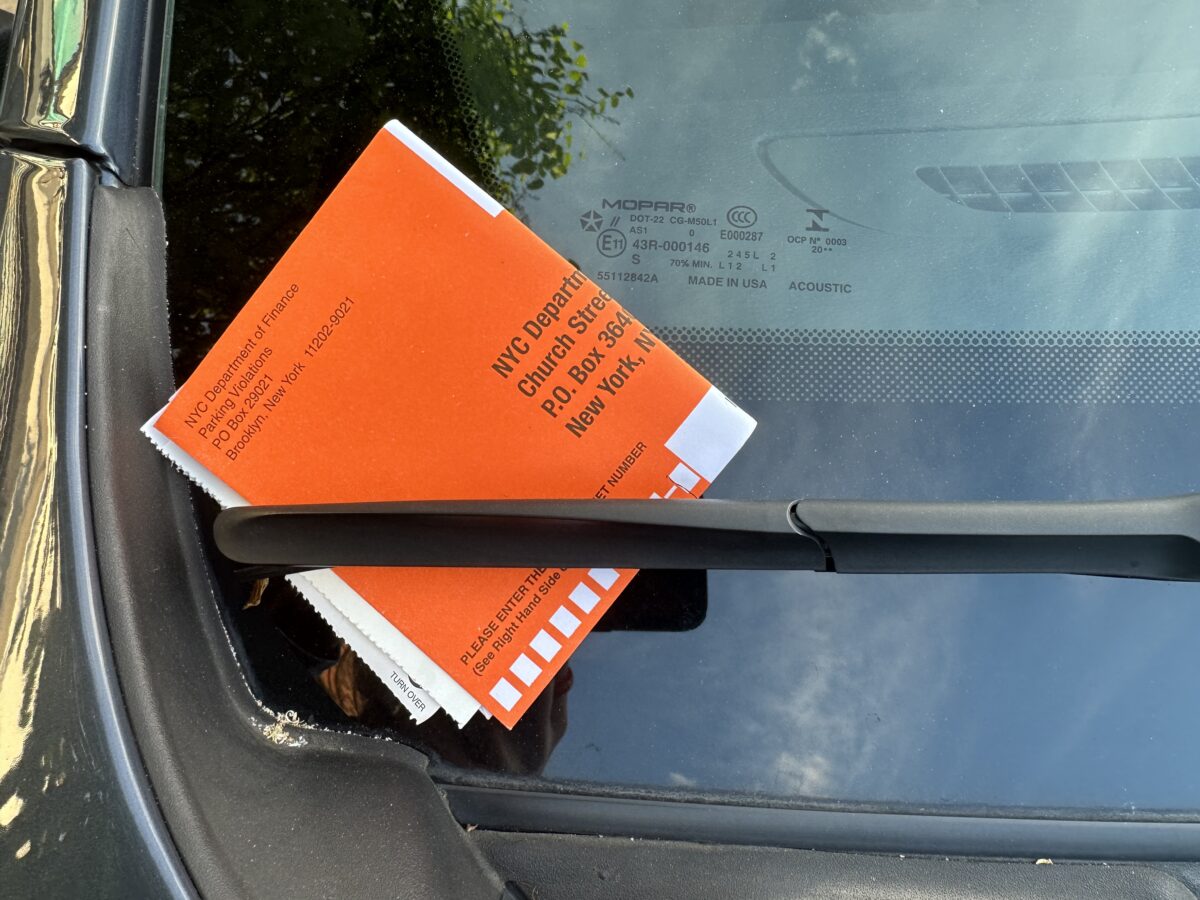

But shortly after their landlord received their back pay rent in the form of a check from the government, they received an eviction notice.

“Even now I still don’t really understand it,” said Sumra, the family’s second oldest daughter, a recent graduate of Columbia University. She spoke on behalf of her family in a phone interview with the Queens Ledger.

To the family, and legal experts, this appears to be retaliation from the landlord for utilizing ERAP to cover their rent during a crisis period. It came as a shock to the family that the landlord wanted to terminate their tenancy after the debt was settled.

On January 15, 2022 the state’s eviction moratorium expired. Since then, eviction rates have crept up, rents soared and homelessness surged in NYC.

Ellen Davidson, an attorney with The Legal Aid Society, says that this is not the first time that a landlord retaliated against their tenants for receiving assistance from ERAP, despite being made whole. Complaints about needing repairs, and subsequent 311 calls that often lead to city inspections and possible fines, are also common triggers for landlords to evict.

“We see that a lot,” said Davidson in a phone interview. “And we see tenants even who are just too afraid to even risk retaliation, and so they won’t complain about pretty dire conditions in their apartments.”

A bill that many say would provide eviction protections for tenants in unregulated housing, while also addressing the affordability housing crisis, is currently sitting idle in Albany. The Good Cause Eviction bill, first introduced in 2019, is sponsored by State Senator Julia Salazar who represents much of northern Brooklyn.

Good Cause legislation would prohibit landlords from ending tenancy without just cause and would set grounds for the removal of tenants. Breaking a lease agreement, failing to pay rent or creating a nuisance for others, would be considered just reasons. If passed, the bill would also cap rent increases to three percent or 150 percent of the Consumer Price Index, whichever is higher.

“It is outrageous that there are thousands of people in our state who are experiencing homelessness in the wealthiest state in the country in one of the wealthiest cities in the world,” said Senator Salazar at a rally promoting Good Cause in Astoria last week. “It doesn’t need to be this way.”

Progressives in the state are currently pushing for Governor Hochul to include the legislation in the already late budget proposal. They argue that without it, tenants who live in unregulated buildings will continue to face skyrocketing rent and dire homelessness rates with limited protection from the state.

Activists rally in Albany for the inclusion of ‘Good Cause’ in the state budget. Photo Credit: HJ4A

This type of regulation already exists in around half of NYC units that fall under rent-regulated status, which includes rent-stabilized units and the few rent-controlled apartments. If you reside in a regulated building, state law protects you from being wrongfully evicted and being disproportionately priced out.

“It’s a weaker regulation than the rent stabilization law in New York,” said Davidson on Good Cause. “But it’s so much more than tenants have now. To be able to have tenants who are currently completely unprotected, have weak protections, would be incredibly important.”

Those strongly opposed to the bill include landlords, realtors and builders who argue that the legislation will lead to higher rents, limit the building of new housing and revamp the market out of their favor. They see it as the renter acquiring more rights than the owner of the property.

Putting Up A Fight

Only a small percentage of evictions end up in housing court. The majority of people ‘self-evict’ by leaving their residence without putting up a fight, according to Davidson. For some, it’s because they don’t know their rights while others have no rights. But more and more tenants are facing ‘no cause’ evictions.

This past February, the Sajid family had their first appearance at NYC Housing Court against Fresh Meadows LLC, who brought a holdover case against them. Unlike a nonpayment case, a holdover case — where the landlord wants to evict for reasons other than nonpayment — is more complicated and rare.

Under NYC’s Right to Counsel law, all low-income tenants brought to Housing Court are mandated a free attorney to navigate the process. Sumra’s family was offered representation by a Legal Aid Society lawyer at their first appearance.

“In the no defense holdover cases, it doesn’t really matter whether the people who were being evicted are good tenants or bad tenants, because the landlord doesn’t have to give a reason,” said Davidson. “And because the landlord doesn’t have to give a reason. There’s no defense to that.”

Prior to the pandemic, close to 85 percent of cases filed in housing court were for non-payments. Only 15 percent were for holdover cases.

The Mental Toll

“There’s normal stress that normal people have. And then there’s stress of where are we going to live,” said Sumra. “When you don’t have money, it just seems like everything, everything works against you.”

The possibility of losing housing took a significant mental toll on the entire family. Sumra’s two younger brothers, who are 13 and 15 years-old, could sense the financial stress in the air without being told. They did everything they could to avoid burdening their parents, even with minor costs.

While Sumra was studying psychology on the pre-med undergraduate track at Colombia, the stress of her family’s housing situation kept her up at night and led her to fall behind in her classes. She recalls more than one instance where asking a professor for an extension came with an explanation that her family could end up homeless. Ultimately, the stress triggered dissociative symptoms and left her severely sleep-deprived.

“At that point, it just kept piling up. And it seemed never ending,” said Sumra. “Like, okay, now what?”

Since the family came into contact with The Legal Aid Society earlier this year, and now have a lawyer representing them, she says a weight was lifted off her shoulders.

Sumra and her older sister now live outside of their family’s apartment and work full time. They contribute what is left over from their own costly expenses of living in New York City to the rest of the family.

“When people are able to stay in place, it is better for that family, their communities and for the city as a whole. People are better able to maintain their health. Kids in school have better educational achievement,” said Davidson. “And people who are working have more ability to get and keep employment when they’re stably housed.”