Cornell and Salvation Army Join Forces to Bring Nutrition to Families

Bilqis Benu, a children services specialist at the Springfield Gardens Family Center, says the garden exceeded her expectations.

By Iryna Shkurhan | ishkurhan@queensledger.com

For the first time ever, the Salvation Army partnered with Cornell and Cornell University Cooperative Extension- New York City (CUCE-NYC) to sprout healthy eating through gardening and nutrition education at a family shelter in Jamaica.

Over the course of eight weeks, families living at the Springfield Family Center met up every Thursday for various cooking classes, lessons on food safety and even a practical lesson on shopping for healthy food on a budget. Parents and their children, as young as four years old, even helped start and maintain the site’s first produce garden from scratch.

On June 21, residents and facilitators of the program celebrated its culmination with a catered meal and certificates of appreciation to those who participated and facilitated the program.

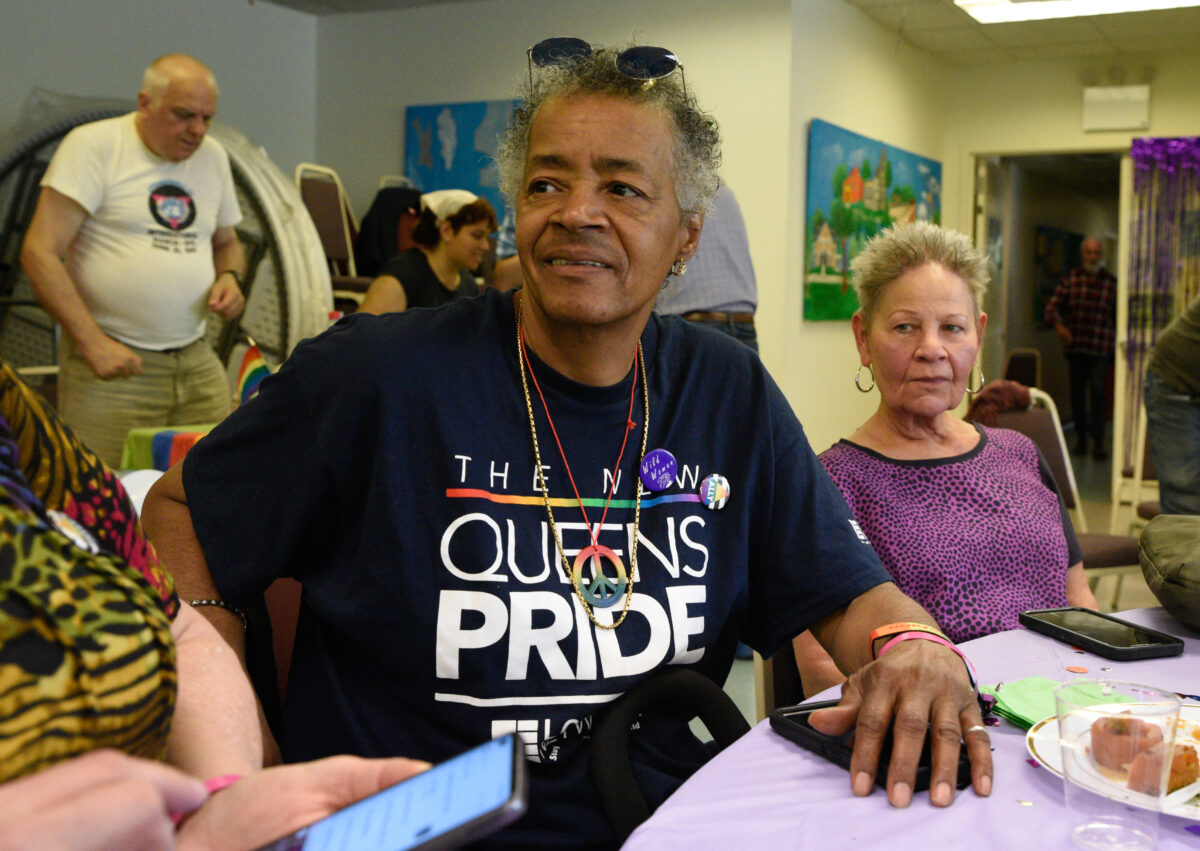

: Program participants and CUCE-NYC nutrition educators celebrated the end of the program with a catered meal.

“The concept was a little garden, so people could feel connected, could still put their hands in some soil and still feel grounded. They could see things grow,” said Bilqis Benu, a children services specialist at the center.

“And then it blew up,” said Benu in describing how the final result exceeded her initial expectations of the garden. She attributes it to Cornell University, and its various departments getting involved in the program to be more of service to the community.

While the program sought to positively impact the lives of participants, data collection conducted by researchers from Cornell was also a crucial element to determine if the program is worth replicating at other shelters in the state and beyond. Paid surveys were distributed to participants at the beginning and end of the program.

“Because everyone here has children, and generally people are concerned about the health of their children, they have the motivation to change their eating habits in their family for the sake of their children,” said Dr. Zeynab Jouzi, a postdoctoral researcher at Action Research Collaborative at Cornell University, who conducted the surveys.

After fostering a connection with the residents to build trust, Dr. Jouzi conducted interviews to gauge what kind of services would be beneficial to help residents transition to permanent housing. She received a range of responses from many first time parents who were living in the center’s transitional housing, with one family per room with a small kitchenette to cook.

Dr. Jouzi’s research focuses on food security and environmental justice with a “leave no one behind” goal.

“My goal in my research is to leave no one behind,” said Dr. Jouzi, whose research focuses on food security and environmental justice. “Generally, vulnerability and being marginalized is going to be a bundle of problems. Many people that are home insecure are also food insecure.”

Kwesi Joseph, an Urban Gardens Specialist at Cornell, said that taking a soil sample at the site was the first step in determining if a garden was possible. He was surprised when a heavy metal test came up negative, a rarity in the city but a clear message that it was safe to grow food. But at that point, they didn’t have enough funds to carry out the program.

Joseph works to start and advance community gardens across the city in his role as an urban gardens specialist at Cornell.

Joseph confided in Dr. Tashara Leak, an associate professor of nutritional sciences at Cornell, about the financial dilemma. That’s when she offered up the help of undergraduate students in her program to apply for grants which would secure money for the garden. The second grant was secured by Benu, who applied on her own.

About half of participants primarily speak Spanish, but the organizers had Spanish speaking educators who simply split up the two groups to provide the same quality of nutrition education. During the educational lessons, children and their parents were also split up for different lessons and experiences.

Derick Edwards, 42, was the only father to participate in the program with his two kids – a nine year old son and an eight year old daughter. Their family has been living in the shelter since last November, and Edwards is in the process of searching for permanent housing.

Derick Edwards was the only father to participate in the program, among a fourteen mothers.

“I noticed that I’m reading the labels more,” said Edwards on the impact of the program. “It might take me a little bit longer to shop, but it’s something that ‘s interesting to me now.”

But despite learning how to save money at the grocery store, a lack of resources combined with a rising cost of groceries, especially healthy produce makes it difficult to implement.

“It’s always been cheaper to go unhealthy. It’s not even like a couple of cents, it’s astronomically more expensive to eat healthy,” he said. “But there are some small ways where you can save money.”

For some parents, the program had an impact on both their eating habits and those of their children.

“So I started doing collard greens but with them. I started doing brussel sprouts, peas, more broccoli, and carrots. Before this, it was just green beans,” said Khadijah Da Don, a mother who resides in the shelter with her three-year-old son. “And now that I learned how to cook certain vegetables, he eats them with no problem.”

“A healthy lifestyle is an expensive lifestyle, but at least you get to live a little bit longer,” said Khadijah who says that SNAP benefits are not enough to cover the cost of healthy groceries, so she has to supplement it with her own money.

The children of the participants got their hands dirty in the garden on site.

“We can’t actually leave, so I feel like the program was like a little escape that we could look forward to, enjoy ourselves, have fun and learn different things,” said Don, who has been living at the center for almost a year with her son, after living in the Bronx her whole life.

While the researchers have not published their official findings yet, since the program will enter a second phase with new participants, some parents expressed gratitude to the nutrition education.

“Changing my meal plan is definitely a plus. So I thank them for that too. Because I didn’t know I like other types of food until now. They made me try something new,” said Don. “And then I ended up liking it.”