Preserving her legacy with street co-naming

By Michael Perlman

mperlman@queensledger.com

Roger Terry, nephew of Althea’s former husband Will Darben with Althea’s great niece Crystal Thorne.

It may be hard to visualize that relatively not too long ago, tennis was a segregated sport, but that largely changed when racial color barriers were broken at the iconic Forest Hills Tennis Stadium.

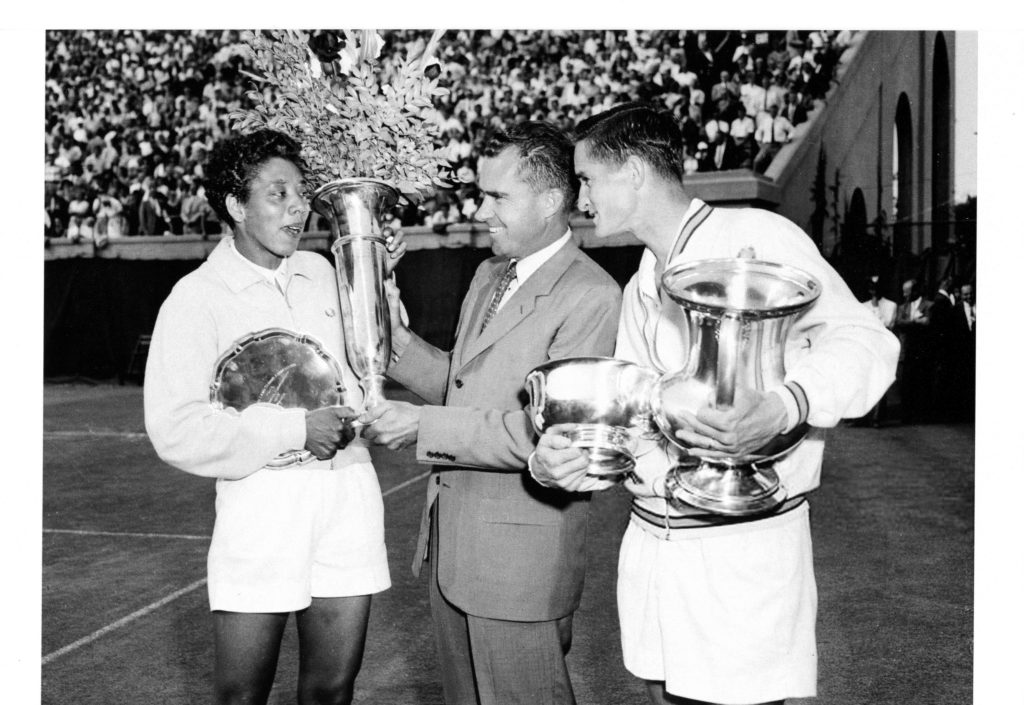

Althea Gibson (1927 – 2003) became the first African American person to win the U.S. National Tennis Championships title in 1957. At the time, Vice President Richard Nixon presented her with the championship trophy.

Althea Gibson, VP Richard Nixon, Mal Anderson, Forest Hills Stadium, 1957. Courtesy of Archives of the WSTC

She was also the first Black player to win Wimbledon that year and received the Venus Rosewater Dish from Queen Elizabeth II.

Then in 1971, she became an International Tennis Hall of Fame inductee.

On August 25, which would have been her 95th birthday, history was made once again with the co-naming of West 143rd Street between Malcolm X and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevards as “Althea Gibson Way.”

Now her legacy will forever be preserved, as New Yorkers and tourists explore a culturally rich New York City landscape.

The location was most ideal, since Gibson and her family lived in a historic building at 135 West 143rd Street.

A block away on 5th Avenue is the 369th Regiment Armory, where she played tennis, and today there are tennis training programs which benefit the community’s youth.

The street co-naming ceremony was heavily attended by family members and friends among fans.

Gibson’s cousin Don Felder had a vision in 2019, and with perseverance, analogous to Althea, it became a reality. He explained, “I had an idea after seeing a cousin of Althea being honored with his name at the intersection of 145th Street and Frederick Douglass Boulevard, ‘The Claude Brown Corner.’ The planning began by contacting the City of New York. The requirements are 100 signatures from residents and businesses on the block and three letters of support. I got support letters from former Mayor David Dinkins, a local church pastor, Whoopi Goldberg and Katrina Adams. The complete package was submitted to Community Board 10. It was approved and a resolution was passed.”

Don Felder holds a photo of Althea Gibson with the Harry C Lee tennis racquet.

Backtracking, Gibson was honored in 2019 with a sculpture near Arthur Ashe Stadium, and she will soon be honored at Forest Hills Stadium during its centennial in 2023, where some of her possessions — including her trophies — will be on display.

Most recently, sports marketing and media specialist Randy Walker republished Gibson’s bio, “I Always Wanted to be Somebody” (1960).

“I would like to see a presidential medal issued to Althea Gibson, as well as see her image on U.S. currency,” Felder said, whose wishes may be granted in 2025 with a commemorative quarter.

Photos courtesy of WSTC

He had much to share about Gibson’s achievements and how it motivates all generations of tennis players following in her footsteps.

“Althea’s perseverance was astounding while realizing the times she played and the racial barriers and obstacles she endured. Althea had to enter from the back of tennis clubs and even change her clothes outside of the clubs before entering, and again leave from the back. At times, she received brutal verbal abuse and attacks, but yet she became the tennis champion of the world who inspired others to persevere in spite of obstacles.”

“I was thrilled,” Felder continued, referencing the moment the sign was unveiled.

“Althea’s nieces came from Virginia to unveil the sign. The drummers did a drumroll as the sign was unveiled and the crowd applauded. My thought is that it has finally been done. After walking the street and getting signatures and letters, we now have ‘Althea Gibson Way’ forever and her legacy lives on.”

A keynote speaker was former USTA President & CEO Katrina Adams.

“It is imperative that we keep her name alive. It’s the next generation that needs to know that before Coco, Venus, Serena, Chanda, me, Lori, Zina and Leslie, was Althea. Why? Because Althea came first,” she said.

Also present was Michael Giangrande, the son of Harry C. Lee & Co.’s vice president.

“They sponsored Althea when no racquet company sponsored Black players,” Felder said. “Michael in his youth would accompany his father to West 143rd Street to visit Althea, and was there after Althea’s win at Wimbledon.” He referenced her greatness.

lthea Gibson’s family who traveled from NY, NJ, Philadelphia, Delaware, VA, NC, SC to honor her.

Roger Terry, Gibson’s nephew, commended her competitiveness in anything, and how she as an older woman would beat him and his friends on basketball and football courts.

“She never wanted to lose in any game,” he said.

Additionally, a young tennis student took the podium and said that when she feels pressure and alone as the only Black girl on the tennis courts, she thinks of Gibson and on whose shoulder she stands on, and she perseveres.

Other speakers included Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine, Councilwoman Kristen Richardson and representatives of the Police Athletic League.

“Althea learned the game of table tennis on West 143rd Street when the PAL closed the street for recreation for the children,” Felder said.

He introduced his family, whose mothers were in the photo display.

“They were taken in 1957 when Althea returned from her first Wimbledon win,” he continued.

Felder, who holds fond recollections of Gibson, said, “I called her mom and asked if Althea can come to my junior high school in Brooklyn as a guest speaker, and she came. She loved her family and made time to come when we called, even as she traveled the world to play tennis.”

He finds her to be a multi-faceted inspiration.

“Althea was a loving human being. She accepted everyone and enjoyed life. She was more than a champion athlete who excelled in every sport, but was also an actress, singer, and saxophonist, which may be unknown to many. She excelled in anything she did, and I’ve learned that I can do anything that I choose, if I persevere.”

She felt at home at the Apollo Theater, where she won second prize in a singing competition in 1943 and received $10 rather than the promised week of singing engagements, but she did not let it dishearten her.

Felder expanded upon the unknowns. “Althea became friends with John Wayne and William Holden as she acted in ‘The Horse Soldiers’ (1959). She loved to perform while on tennis tours. She played basketball and was a bowler, and was the first Black woman to golf in the Ladies Professional Golf Association. She also sang on ‘The Ed Sullivan Show,’ was on ‘What’s My Line?’ and taught tennis to inner city children.”

As Felder toured the grounds and Clubhouse of the West Side Tennis Club, he could feel Gibson’s presence.

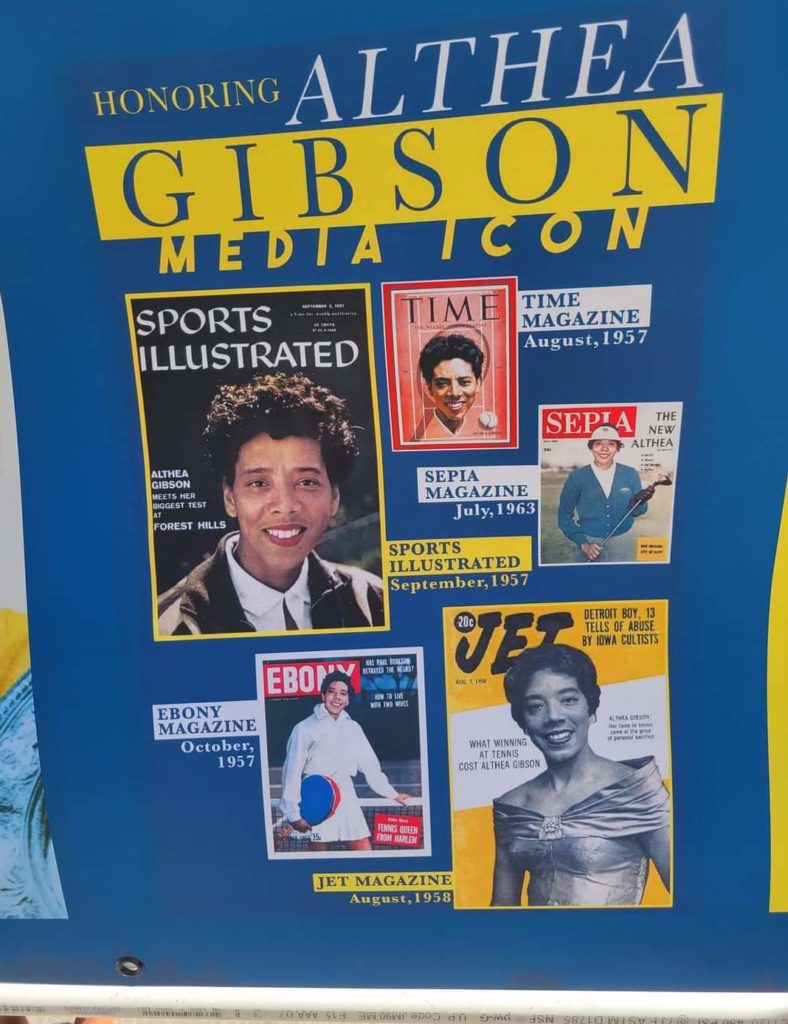

Althea in the media display.

“I am in awe that I am walking where she walked and played, gained recognition, and became champion and broke down racial barriers,” he said. “I believe that she is pleased that her family member now sees where she worked and played and loved to be.”

Despite her passing, the public can continue to learn from her accomplishments in the face of adversity.

Felder explained, “Many young people and adults still do not know who Althea Gibson was. She was a great American who overcame many obstacles and became a great ‘Somebody’ as she wrote in her autobiography ‘I Always Wanted to be Somebody.’”

The street co-naming united the community as well as her family, generating a sense of pride, according to Felder. “Althea’s name on the street in Harlem tells other young people from the community that they too can achieve their goals and dreams,” he said.