By Celia Bernhardt | cbernhardt@queensledger.com

After doing the rounds at the film festival circuit, Tyrel Hunt’s new film, “The Sound of Southside,” is available for all back at home to watch online.

“I wanted to show a different side of Queens that maybe a lot of people haven’t heard of,” said Hunt of the project.

A tribute to jazz in Jamaica, Queens, the film follows a young man named Maliki finding his path after coming home to the neighborhood as a college grad. Maliki, played by James Ross, embarks on a journey to reopen his late father’s jazz club. Along the way he falls in love with an aspiring actress named Afeni, played by Hunt’s wife Amanda Hunt.

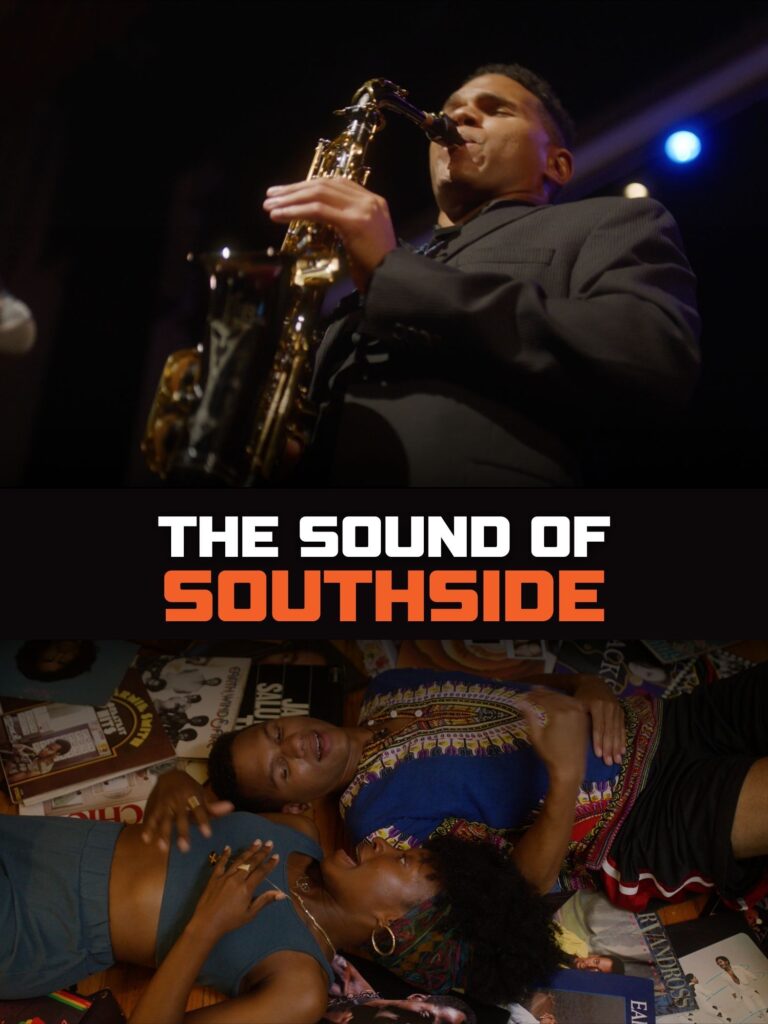

“Sound of Southside” poster.

Hunt, who grew up in Rosedale and now resides in Jamaica, was never much of a jazz kid himself growing up. But working as the director of marketing and communications at the Jamaica Center for Arts and Learning, he was continually exposed to the genre through the organization’s programming. It inspired him to dig into the history and presence of jazz in the neighborhood.

“I wanted to highlight that the community has such a rich jazz history. And I wanted to make this movie because I wanted to make sure that didn’t get displaced,” Hunt said. “And [so] when people look at the community years from now, they’ll still be able to remember that so many great jazz legends have lived in the borough.”

Centering that message in Jamaica, particularly, is important to Hunt, who says that the region is underrepresented in pop culture. “I think it’s a shame because so many great people have come from the community. But I think a lot of times when you see Queens on TV, and in film…it’s the more commercial part of Queens. And when you do see Southeast Queens, it’s usually connected to hip hop.”

Always lurking in the background of the film, driving the plot forward, is the issue of gentrification in Jamaica — something Hunt feels day-in and day-out in the neighborhood.

“A lot of community hotspots that people found value in…just aren’t here anymore, or are leaving,” Hunt said. “One example of that is the Jamaica Multiplex, the movie theater on the corner. Just places like that are staples in the community.

“I think along with that comes people being displaced,” Hunt continued. “People not having anything productive to do, or places to go, or seeing their culture and things like that represented in the community. So that was all a concern for me.”

Though his primary medium is film, Hunt first wrote the story as a novel during the Covid lockdowns.

“I had to figure out a way to stay creative,” he explained. “I didn’t think [writing it as a book] would work, because it’s hard to write how music sounds…but I had a lot of time on my hands. And it was really cool. I think the best thing about writing a book is there’s no limitations— compared to film, where you have to think about personnel and budget, all of those things. With the book, I was able to really write a more expansive version of the story.”

James Ross as Maliki and Amanda Hunt as Afeni.

But Hunt had always envisioned the story in film; in 2021, he was finally able to make it a reality.

Hunt shot the film over the course of just two weeks. Every step of the way, the process was a community effort.

“That was due in part to the fact that we didn’t have any permits,” Hunt said.

The team still shot a good deal of footage in public spaces, and sometimes in spaces that businesses or organizations lent out in support of the film. “Sound of Southside” characters can be seen making their way down a bustling Jamaica Avenue, walking through Rufus King Park for a peaceful respite, or shopping at the legendary VP Records.

“It felt very collaborative,” Hunt said. “I think that the rhythm of the film is something that we share with the community.”

As far as casting, Hunt said, “There were a lot of actual jazz musicians who were basically playing themselves in the movie. These are people I’ve met working at JCAL, doing these jazz events, and just kind of being in the community.”

One particularly momentous scene near the end of the film, depicting a performance and a room packed with listeners, was shot in one of JCAL’s own spaces. The audience in the scene, meanwhile, was composed entirely of people Hunt knew from his own community.

“They were family, friends,” Hunt said. “It was like a mini-reunion.”

Even before his professional pursuits, Hunt says he was always exposed to the arts in Rosedale and Jamaica.

“I was always writing short stories, poetry and all of that stuff. And it was always shaped by my community and my experiences. So I’m grateful for Rosedale and the community for helping me become who I am—and living in Jamaica is kind of an extension of that right now.”

Both Hunt’s film and novel are available to purchase on Amazon Prime.

Tyrel Hunt