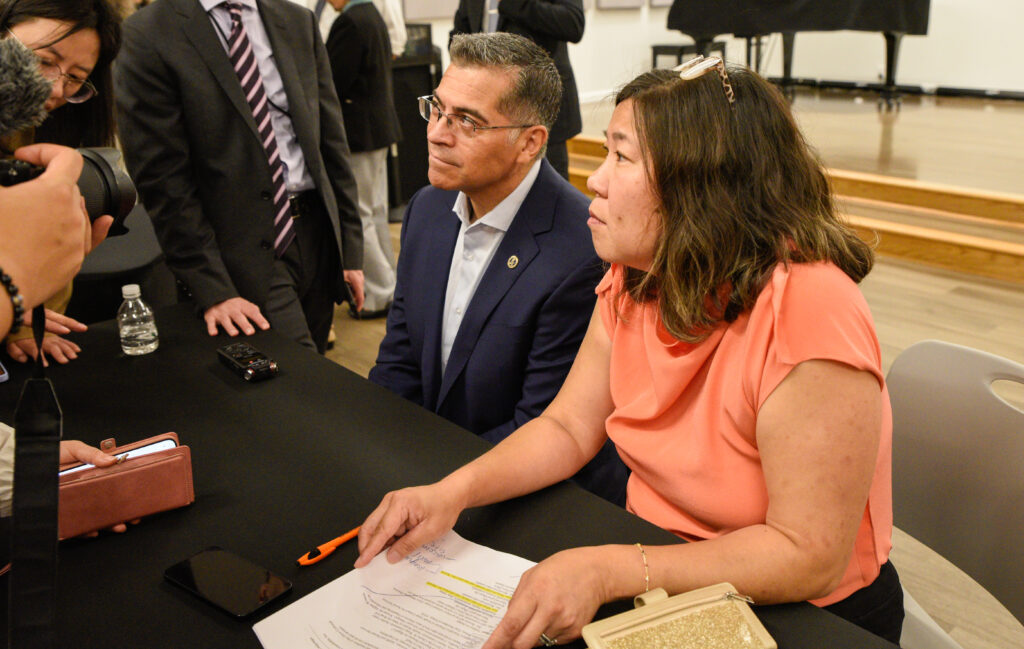

The U.S Secretary of Health joined Congresswoman Meng and local leaders in Flushing for a roundtable discussion. Photo by Iryna Shkurhan.

By Iryna Shkurhan | ishkurhan@queensledger.com

The U.S Secretary of Health and Human Services, Xavier Becerra, visited Flushing on June 30 to join Congresswoman Grace Meng and immigrant advocates for a roundtable discussion on language access and culture competency in healthcare.

The dialogue centered around how to better serve immigrant communities, especially those who speak languages of limited diffusion, with physical and mental health resources in their spoken language. Advocates say that current care and availability of public health info for immigrants whose primary language is not English or Spanish falls short, and can be disastrous in emergencies.

The issue is especially consequential in Queens where immigrants speak over 160 different languages, making it the language capital of the world according to the World Economic Forum. Close to a quarter of New Yorkers, about 1.8 million residents, are also not proficient in English, according to city data.

“80 percent of our patients want their care not in English. And we’re not talking about interpretation or translation, those can be helpful on the edges but what they really want is their care with someone who speaks the languages,” said Kaushal Challa, CEO of Charles B. Wang Community Health Center, which focuses on primary care in various offices across Flushing and Chinatown. “I’m not going to say that you cannot establish trust if you don’t speak the same language, but it’s a major, major component.”

The discussion, held at Flushing’s Glow Cultural Center on 41st Ave, was especially timely, as June’s Immigrant Heritage Month comes to an end. Meng and Becerra were joined by representatives from several community advocacy groups, including South Asian Council for Social Services and Women for Afghan Women.

“I remember growing up and translating for my parents when they needed to see a doctor,” said Secretary Becerra, who was confirmed into Biden’s cabinet in March 2021 as the first Latino to hold the office. “While I am proud to have been able to help, no child should have to feel the weight of translating complex medical terminology. And no parent should have to share their private medical history with their young child.”

Since stepping into the role, he has worked with state governments to push providers and insurers to increase language access. He says he is no stranger to working with immigrant communities after representing the downtown Los Angeles area as a congressman for over two decades.

Meng, who represents a significant chunk of northern Queens, which includes Flushing, Fresh Meadows and Forest Hills, previously worked with Becerra to open the city’s largest vaccination site in the center of Elmhurst in 2021.

Everyone agreed that during the pandemic, immigrants whose primary language is not English had difficulty even getting the most basic information on Covid-19, such as where and how to get tested.

“We found that, especially in the beginning of the pandemic, how limited access to language services really hurt folks,” said Theodore Moore, Vice President of Policy at New York Immigration Coalition. “And even in New York City, where you have one of the best language access policies in the entire country, we couldn’t get information past English or Spanish.”

City data also shows that multilingual immigrant communities in the outer boroughs were hit the hardest by Covid-19. Central Queens neighborhoods such as Corona, Elmhurst and Jackson Heights, where more minority and indigenous languages are spoken became the “epicenter of the epicenter” with thousands of cases within the first month of the outbreak.

Meng’s proposed legislation, COVID-19 Language Access Act, would require federal agencies to translate memos in the top 20 spoken languages during times of emergency. Two language access bills, spearheaded by Councilmember Julie Won, passed in the city late last year. The bills were also born out of an emergency, when warnings about the severity of flooding from Hurricane Ida were distributed in English, resulting in the deaths of eleven Queens residents who died when their basement apartments flooded.

“We need more authority to be able to tell health care providers, health insurance companies, that they must do a better job of communicating with their patients,” said Becerra. “And with those additional authorities that Congresswoman Meng could provide us, we have more leverage to try to move in that direction.”

Both representatives expressed commitment to increasing accessibility to healthcare for immigrant communities. Photo by Iryna Shkurhan.

Moore also noted that there is rarely accessibility in languages from the African continent. And indigenous languages, which are spoken by many new migrants arriving from Central and South America, are even harder to find translators for.

To address this inequality, his team created three language access cooperatives: one for African languages, Asian languages and one dedicated to Central and South American indigenous languages. Immigrants who need access to information in a language of limited diffusion, may not be able to get it from city services, but can rely on groups like New York Immigration Coalition to support them with translated resources.

A big chunk of the discussion was devoted to mental health, which has risen to a level of prominent awareness and resulted in an increase in funding from federal, state and local governments. While Becerra pointed out that the federal government does not control or manage healthcare, it does have the power to work with states in guiding new initiatives.

He discussed the wide impact that 988, a centralized phone number for mental health crises that connects people with local suicide and crisis hotlines, has had across the country. Over two million people called or texted 988 within its first six months of operation, indicating a significant demand for crisis level mental health assistance, according to officials.

Some call centers have Spanish speaking staff members, but an official Spanish speaking line is still in the process of being established. Becerra said that in the future, he hopes the service will be able to offer more languages.

“A lot of the times when providers are talking to the patient, they’re talking to translation services, they’re not looking at the patient’s eyes,” said Carmen Garcia, Community Health Worker at Make the Road. “And that is very important because those people want to be seen and we also want to see eye to eye and understand.”

In her experience working with patients who speak a different language, she notices that translators do not always translate in the way that she asks her questions. Garcia says that she will use motivational interviewing techniques and applications to try to get to the root issue of patients’ distress, which get lost in translation.

Garcia, and other advocates present, shared that expanded recruitment and retention of healthcare staff that speaks the languages of the community members they serve should be prioritized. Besides language, an awareness of cultural backgrounds and circumstances can be just as important when delivering healthcare services.

“Prioritizing and promoting equitable access to language assistance for health services to people with limited English proficiency is crucial for our immigrant neighborhoods, and I am excited to partner with Secretary Becerra on this effort,” said Congresswoman Meng. “I thank the Secretary for returning to Queens to shine a light on the importance of language accessibility in our healthcare system.”

Congresswoman Meng also introduced the bipartisan Mental Health Workforce and Language Access Act in 2021, which would establish a grant program to deliver federal funds to community health centers to recruit and employ bilingual behavioral health specialists. The current retention gap has been attributed to a lack of competitive salaries compared to private hospitals, and high rates of burnout in the healthcare field.

“It doesn’t matter if you have access to coverage, if the person next to you doesn’t,” said Moore. “Quite frankly, you’re in the same boat as them and we’re all in this together.”