By Stephanie Meditz

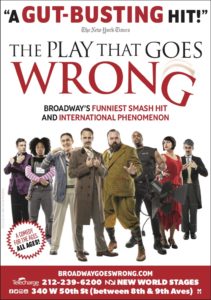

Photo courtesy of “The Play That Goes Wrong” via Facebook.

Everyone knows the saying, “The show must go on.”

The players in “The Play That Goes Wrong,” who power through their scenes despite a hazardous set, missing props and unconscious actresses, embody it in a way that makes audiences howl with laughter.

Written by Jonathan Sayer, Henry Lewis and Henry Shields, the 2012 play follows the Cornley University Drama Society’s opening night of “The Murder at Haversham Manor.”

The set, however, is incomplete and falling apart in every imaginable way.

The play begins with a pre-show of sorts in which stage manager Annie and lighting and sound operator Trevor tinker with the set, replace floorboards, put a stubborn mantelpiece on the wall and force a perpetually open door to close.

They even solicit an audience member onstage to hold the mantelpiece in place and the door shut while the two promptly run offstage.

Director and serious thespian, Chris Bean (played by Chris Lanceley), then assures the audience that his directorial debut will be a treat compared to the drama society’s former productions, such as the one-man show, “Cat.”

The play within the play, “The Murder at Haversham Manor,” begins with Charles Haversham (Chris French) lying dead on the night of his engagement party to Florence Colleymoore (Maggie Weston).

Also present are Florence’s brother and Charles’ old friend, Thomas Colleymoore (Brent Bateman), his butler, Perkins (Adam Petherbridge) and his brother, Cecil Haversham (Alex Mandell).

Knowing that someone in the group must have committed the murder, they solicit the help of Inspector Carter to find out whodunit.

At the start of “The Murder at Haversham Manor,” the audience sees that Annie and Trevor have won their battle with the door: it will not budge when the players try to open it.

Not only that, Charles Haversham is extremely mobile and sentient for a corpse – he visibly inhales after Thomas declares that he is not breathing and squirms when other players step on his hand.

When Thomas and Perkins try to carry Charles’ body offstage on a stretcher, it rips, so the two pretend to carry it while the corpse slug crawls offstage.

The defective set and players slipping out of character are laughable evidence of a production going south, but “The Play That Goes Wrong” especially succeeds in its hilariously convincing slapstick.

During Florence’s interrogation by Inspector Carter, Thomas throws open the now functional door, knocks Florence unconscious and schleps her body offstage.

Arguably the funniest recurrence throughout the show, however, is the bottle of paint thinner in place of scotch.

Since the show must go on, the players are trapped in a vicious cycle — they drink the paint thinner, spit it out and comment on the high quality of the “scotch” while visibly recovering from the blow to their mouths.

The spit take has long been used in comedies, but it especially works in “The Play That Goes Wrong” because the players still deliver their lines after each one to pretend nothing went wrong.

The play’s other mishaps have a similar effect — they are funnier because “The Murder at Haversham Manor” is not intended to be a comedy, so audience members must suspend their disbelief and watch it as such.

The audience laughs when Dennis, who plays Perkins, mispronounces “cyanide” as “ky-uh-needy” precisely because he is mortified.

After intermission, a flustered Chris Bean begs the audience to stop laughing and take his play as seriously as they would “Hamilton.”

The audience laughs on, both because of the appropriate pop culture reference and because he is still somehow taking the play seriously after its disastrous first act.

Overall, “The Play That Goes Wrong” is as funny as it is because people like to see just how far these players will go to ensure that the show goes on.

Or, simply put, seeing people get hurt in elaborate and unlikely ways is plain hilarious.

The actors in “The Play That Goes Wrong” are exceptionally talented, not only because they perform this riot of a show without laughing, but because they must be locked into two separate characters.

The actors transform into their respective members of the Cornley University Drama Society, and then they must play that actor’s role in “The Murder at Haversham Manor” in a logical way based on their traits.

The current off-Broadway cast does a stunning job of remaining locked into their roles – the only breaks in character are written in the script.

Alex Mandell, whose character, Max, plays Cecil Haversham and Arthur the gardener, gives an especially vibrant and interactive portrayal of a lovable fool who is just happy to be in front of an audience.

The set is also successful in its astonishing failure — the furniture falls apart at just the right time to leave the audience laughing out of incredulity.

This is an impressive feat by the real-life stage crew because the deliberately malfunctioning set drives the comedic timing that dictates the play’s effectiveness.

Because the successive mishaps are meticulously choreographed, “The Play That Goes Wrong” is a difficult show to put on, and the current off-Broadway run at New World Stages is an immense theatrical achievement.

To find out who killed Charles Haversham or, more likely, to see what else can possibly go wrong, buy tickets for “The Play That Goes Wrong” here or through Telecharge.

Before the performance, make sure to grab one of the show’s signature cocktails — just make sure it isn’t actually paint thinner.